Forbidden Fruit —

Tales From North Korea

Not under foreign skies

Nor under foreign wings protected

I shared all this with my own people

There, where misfortune had abandoned us.

—Anna Akhmatova, Requiem, 1961

Take it into town, happy, happy

Put it in the ground where the flowers grow

. . .

Shiny happy people laughing

—from REM's 1991 hit, Shiny Happy People Laughing

Happy! Sad!

In North Korea, you must be happy. Or you must be sad. Not in an ordinary way, but extremely. It is written.

Nowhere else on earth are people so happy. The country has a joy index that measures it. Nowhere else are people so smiley. Their national television station shows them that they live in the happiest place on earth.

When they lose what they love the most, a dear leader, they are then the saddest people on earth. Nothing can contain their grief. It is that simple, that pure. Even the children cannot contain their sorrow.

The happy, or sad, crowded squares of North Korea are, of course, meant to showcase its strength and unity as a nation. The onus such outpourings put on ordinary, tired, and often hungry people, to line up and spend their energy, their day off, in a public square when they aren’t eager to do so, is a fraught matter. Every person knows his and her exact placement in all events, including the children, and one’s absence at any time is noted and punishable.

Here Is a Story About North Korean "Stage Truth"

It is three months after the death of eternal leader Kim Il-sung, and the country is still strangled in grief. The dirge from the omnipresent loudspeakers never lets up. Every day the mourners — that would be every man, woman, and child — place fresh flowers at altars set up all over the city, in schools, factories, and offices, and give way to their grief with loud sobs.

The authorities tally their visits and the sincerity of their sobs.

By now, fresh flowers are scarce. They've all been picked. People are forced to climb the mountains to look for wildflowers. It is dangerous. The monsoons have turned the hills into thick, dark swamps, which makes the snakes come out. Some people fall off the soggy cliffs and die. A child gathering flowers was bitten by a snake and died. His mother has buckets-full of sobs for the dear leader. Grieving, flower picking, daily homage must last a full year.

Hong Yeong-pyo, Comrade Inspector for the Union of Enterprises of the Bowibu (secret services), will not last that long. A thin, frail presence in his fifties, ravaged by a liver disease not under control, he is further ravaged by a psychic pain so strong it kills him. How can he bring that son of his to his senses? That son, Kyeong-hun, who has been causing him grief for a year!

(But hadn't he wanted to breed out his rigid tendencies? Isn't that why he married Sun-Shil, to have offspring with some of her artistic sensibility?)

A year ago Kyeong-hun committed a heinous crime that would have landed him in a political prisoners' camp, but for his father's position in the Bowibu. Kyeong-hun was serving in the military along the border with South Korea. He was in charge of an acting troop, and the authorities deemed his play rehearsal "mediocre."

He wasn't believable enough. His offense was "lack of stage truth."

The play was The Bottomless Mess Tin, in which he had to pretend to be eating all kinds of delicious food, while his stomach was "as hollow as an empty cellar." He improvised a comedy skit, right on the spot, which he called It Hurts, Ha Ha Ha!, followed by It Tickles, Boohoo! This got the troops laughing. They were so hungry they joked about their navels trying to kiss their spines. For punishment, they were forced to do drills on their empty stomachs.

What is worse, Kyeong-hun befriended Kim Suk-i, whose family is under surveillance. Her father is a political prisoner whose crime was to say that Kim Jong-il had taken a second wife. Because a criminal sentence carries through for the next three generations, Suk-i will never have a good job and will always be under suspicion.

Kyeong-hun was seen holding Suk-i's hand on the mountain cliff while trying to find some wildflowers for the day's forced ritual mourning. He had what looked like a liquor bottle in his other hand (it wasn't, and he held Suk-i's hand to steady her on the cliff).

Yeong-pyo is shamed before his Bowibu comrades as his son's new crime is noted, that of frolicking instead of grieving. His shame works itself into a rage against his worthless son.

Angry words fly when he gets home. Yeong-pyo gets out his gun and threatens to kill Kyeong-hun. Stunned, the son looks at his father. Go ahead, he says. Shoot me. Don't you know this entire mourning ritual is all just "stage truth"? That we are all great actors? That you're so good at it because you've had 58 years of acting lessons?

In a panic over his son's insolence, Yeong-pyo leaves in haste because he is responsible for the set-up at one of the altars. It must be properly lit, halo-like around the leader's face. He has to monitor how sincere the the current crop of mourners' "drawn out chorus of wailing" is, which can be heard above the strong gusts of wind and rain.

There at the altar he sees Suk-i's mother, the very one whose husband languishes in a prison camp and whose family is near starvation. Great Leader, Father! she cries loudly. Yeong-pyo is confused. This is too much! How can her tears seem so real when the man she loves is dying in prison?

Just then he hears a voice coming from his own head. Stage truth, it says. Could such wailing really come from Suk-i's mother? Stage truth, comes the voice again.

Could his son be right? Was his whole life an act? A lifetime of good acting, with his final act a bullet to his temple.

This story, On Stage, is from a collection of seven short stories written by the North Korean writer Bandi and translated by Deborah Smith. The slim volume is entitled The Accusation. To read the stories is to feel like you have been given an entree into the no-man's land that is private life in North Korea.

The name Bandi is a pseudonym. It means firefly in Korean. We know nothing about Bandi, about him or her; we'll say “he” and “him." He is still in North Korea and may stay there incognito, but in 2014 his short stories were smuggled out alive. To the stories, he appended these words:

Fifty years in this northern land

Living as a machine that speaks

Living as a human under a yoke

Without talent

With a pure indignation

Written not in pen and ink

But with bones drenched with blood and tears

Is this writing of mine

...

Reader!

I beg you to read my words.

Judge for yourself the amount of "stage truth" in the video below of mourners at Kim Jong-il's funeral. The mourners don't exactly look like they are suffering. They look okay enough. But as I watched and read more about the totalitarian grip on these people, about how quickly one's fate can become a horror story, about how a loyal life can end in banishment, I found myself affected, feeling for a people who are forced to act unnaturally as a matter of course.

Eobi! Monsters!

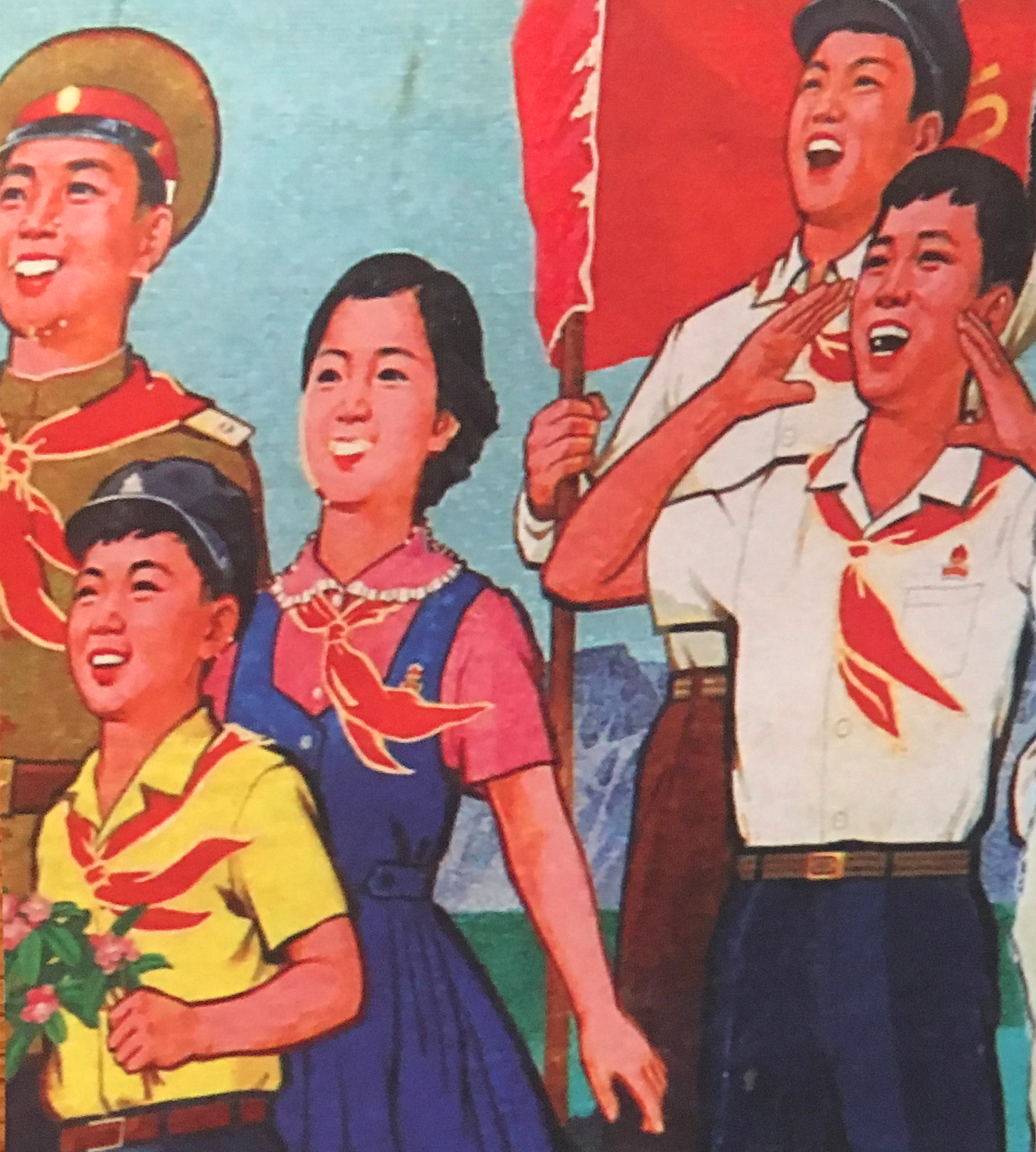

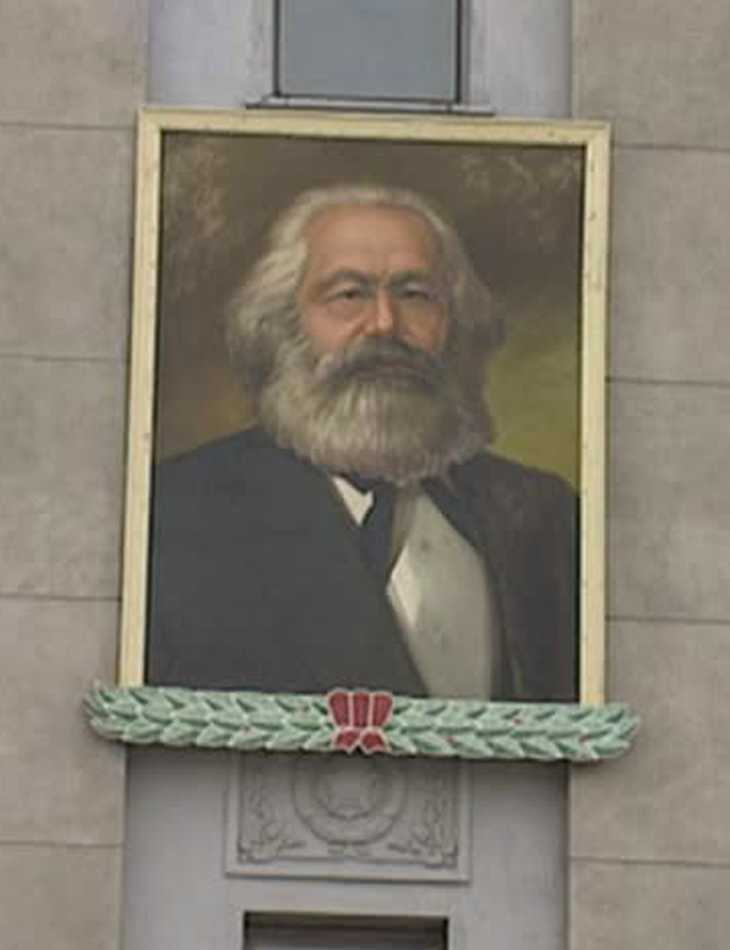

In Bandi’s City of Specters, it is the day before the National Games in Kim Il-sung Square in Pyongyang. Giant portraits of Karl Marx and Kim Il-sung hang from the Square’s buildings.

More than one hundred thousand people will file neatly into the Square to celebrate the eternal leader's birthday, to take part in the rally and the games.

Gyeong-hee picks her two-year-old up from nursery school after work. Little Myeong-shik clings to his mother on the commuter train home. His teacher singled him out for his frail character because he awoke from a nap screaming “Eobi! Eobi!” The Eobi are scary creatures who toss disobedient children down a well.

Gyeong-hee is no wimp. She has an important job in the Propaganda Department and lives in a fifth floor apartment with large windows overlooking the Square. But she is bothered by the teacher’s comment — what does she know?

It all started a week ago during a citizens’ rally to prepare for Kim Il-sung’s birthday celebration. Although Myeong-shik was sick with a fierce fever, Gyeong-hee strapped his burning little body to her back because she was required to attend.

Her group was positioned just below the “glowering gaze” of Karl Marx, who in the wet haze of the evening looked ghost-like. It made Myeong-shik cry. The Eobi will get you if you’re bad, Gyeong-hee told him, in an effort to quiet him. He looked up at the giant portraits and thought she meant that they were the Eobi. He started convulsing.

Since then, he’s had similar episodes at home. Right outside his living room windows are the giant portraits — the Eobi — monsters!

This is dangerous, because Kim Il-sung’s portrait hangs in every room in North Korea. To calm him down, Gyeong-hee closes the double curtains over the transparent white curtain liners.

Closed curtains are not allowed, however, cetainly not on the Square, where the buildings must all look uniform from the outside, especially for the upcoming big event. Only the transparently thin white curtain liners are allowed over any windows facing the square.

Home from work and the nursery, Gyeong-hee gets a visit from Comrade Secretary. Why are your double curtains drawn? she asks. Why are you trying to block out the square? You know what an important celebration this is!

Gyeong-hee’s feeble explanation of her son’s illness and fear of the portraits only increases Comrade Secretary's indignation and suspicion.

But Gyeong-hee is a loyal patriot, as everyone knows! Comrade Secretary is suspicious of her, of all people? The daughter of a martyr for the state? Can’t she understand? Tomorrow during the ceremony she promises her windows will be uncovered.

Her protestations are useless. Her son's fears are a sign of deviance. The Secretary’s job is to weed it out. The violation is duly noted.

Gyeong-hee's husband then arrives home, unhinged. He was summoned during work to the Department of Information, where he was questioned about the double-drawn curtains. When he told them about his toddler's silly fears, they informed him that a child’s fears come from the mind-set of the parents.

In a fearful rage at home, he rips down the double curtains. Heavy rain lashes against the bare windows, and the electric street lights flicker on and off all night long. Myeong-shik sleeps fitfully, between bouts of crying, and Gyeong-hee sleeps not at all. And they must soon be ready for the biggest celebration of the year!

The rain does not let up until 10 a.m. It is followed by incessant radio broadcasts, heard at every bus stop and subway station and in every building, for all participants, without exception, to assemble at their designated assembly points.

And then a miracle began to unfold. One by one, columns began to form in the square, neatly divided like blocks of tofu. Each column formulated new blocks in rapid succession, as though the phrase without exception were a long steel spit pushing through the city, skewering people in bunches and delivering them promptly to the square. (City of Specters, p.55)

One hundred thousand people assembled neatly within forty-five minutes!

Afterwards, Gyeong-hee and her family are charged with “lack of fervor.” The Department of Information clears out their apartment before they have time to do so themselves. A truck picks them up at midnight for a ride to the train station. A department officer will accompany them on the train; they are being sent far, far away, so far they won't know they're still in North Korea. The verdict against them is:

Neglecting to educate their son in the proper revolutionary principles, with a negative effect on the National Day ceremony . . . The accused are therefore guilty of jeopardizing the preservation of our Party’s ideology. (City of Specters, p.57)

If these stories seem extreme, they are. They are also truthful. You cannot get 100,000 people in neat rows in 45 minutes without robotic mental work on each person’s part. As Gyeong-hee finds out, the preparation starts seriously in nursery school. Her right to her relationship with her two-year-old is superseded by the state's right to use him as a propaganda prop.

Only in researching North Korean life did I grasp how early the indoctrination starts. Not as older children, but as toddlers the boys and girls already know the importance of showing their submission to the leader. They may not understand, but they know they and the leader are bonded.

Behind the Concrete

People who visit North Korea often want to break through the wall, look inside into the "real” North Korea. I think what they are allowed to see is the real North Korea — the big empty show put on for visitors is the big empty show they really live in.

If it's hardship or political resistance the intrepid visitor is curious about, the afflicted also live in that empty place, alone with their poverty, or isolated in some camp where their suffering and starvation are never seen by the outside world. Only the elite in Pyongyang have any worldliness. Almost no one has the Internet.

No wonder the rules are so important. They're all there is.

The incessant (and imploding) ideology, the robotic mass expression of emotion, the claim on one's psyche to be nothing but an extension of the state when the state itself is mainly an abstraction whose rewards are illusive, are pressures that erode brain function. Human beings reach a point where they can handle such pressures only if they live at a remove from their own private perceptions.

Emotions get contorted, like they did for Yeong-pyo in Stage Truth. He knew his son wasn't really a criminal but he was hapless, hopeless, in the face of the state. The pressure to perform for the Bowibu wrecked his ability to function effectively in private. How should he proceed with his son? What is important? He knew only that he would lose his son if he kept getting noticed by the authorities, and the whole family could get marked for life or sent away. (And they do get marked, by Yeong-pyo's final act.)

Escape Route

In Record of a Defection, Il-cheol is fated never to make it into the Party ranks. When he was a child, his father had been sent to a prison camp for not relinquishing to the state as humbly as he should have the few acres he had made fertile over the years with his own sweat and blood. Il-cheol, his mother and brother were banished “under armed guard to . . . distant parts” near the Chinese border, never to see his father again or know where he is.

Now grown, Il-cheol has a loving wife, Nam Myung-ok. They met at the technology factory, where they had decent positions and where Il-cheol is known for his inventiveness. Myung-ok is proud of him.

But why is her husband always turned out of important meetings? He is “humble and diligent despite his extraordinary mind ...,” she thinks. If only he could join the Party! Then his true worth would be known to all.

Her beloved nephew Minsu visits her in tears when he finds out he is denied the position of class president. But he's brilliant, like Il-cheol, first in his class!

Myung-ok reaches out to a friend of hers who works at Minsu's school. The friend asks her superior, and the news is not good. Minsu will never be class president and will never reach the rank of Boy Scout, the path for the brightest students like himself to a secure future in the Party.

Myung-ok does not accept that neither Il-cheol nor Minsu have any real standing. She does not want her husband to go through life “a gemstone scuffed by ignorant feet.” Her love is mixed with sympathy and foreboding.

She tries to remedy things. The local Party Secretary lives downstairs — he might be able to help!

She asks the Secretary to put in some good words for Il-cheol and look out for his interests. Then his family would not be scrutinized as potential criminals.

But as it happens, the Secretary has no interest in Il-cheol, it's Myoung-ok he is interested in. His visits increase, often at night when Il-cheol must stay late at the factory, and Myoung-ok has no recourse against him. She secretly obtains birth control pills because she has made a decision not to bring a child into a world that will condemn him or her.

Meanwhile, their apartment has come under surveillance ever since a woman downstairs reported that she saw someone who looked "distinguished" going up to Il-cheol's apartment. A non-Party worker would never get a distinguished visitor.

Myung-ok knows that Il-cheol has a tarnished family history, but she never knew the details. She again reaches out to her friend at Minsu's school, who agrees to covertly pull the family's file for Myung-ok. She reads:

Lee Il-cheol

Family: Class 149 [traitor]

Evaluation: hostile element

Father: Lee Myeong-su

As a prosperous farmer under the Japanese colonizers, harbored resentment toward the Party's agricultural collectivization policy ... in village xx, district xx, Wonsan. Punished as an anti-Party, anti-revolutionary element.

Mother: Jeong In-suk

Died ... from resentment toward her husband's punishment.

(Record of a Defection, p.27)

Hostile element, anti-Party, anti-revolutionary?! Myung-ok finally understands: Il-cheol will always be an outcast. How can a life devoted to work and following the rules, how can a mind so capable, count for nothing?

So they will escape. They will take a train to the coast, where Il-cheol hid a dugout canoe for this purpose. Minsu's family will join them there. In the dead of night the canoe will "bear the fate of all their lives."

There is ... great peril in this. We might easily be shot by the coast guard or a patrol boat ... still ... we choose to bet our lives on this chance. ... perhaps the hand of a rescuer might draw us to some new shore. Otherwise, we can only hope that our canoe on the vast blue will mark this land as a barren desert, a place where life withers and dies! (Record of a Defection, p.45)

Dark Terrain

There are seven stories in Bandi's volume, different kinds of lives on different social levels. Like the stories above, all are enshrouded in a weary totalitarianism that no longer has a center. That’s an old-time word, totalitarian. But it’s the correct description, and it's especially cruel in North Korea. There is no leeway for a suspected offender, and it doesn't matter if the charges are false.

I’ve seen drawings by political prisoners in North Korean prison camps that recall an inventive, Nazi-style cruelty for its own sake. The drawings are so awful I’ve not put them here, but you can see for yourself what goes on in the prison camps scattered around the country. Everybody there knows about them. Whole families wind up in these places. Children are tortured along with their parents.

Bandi is an insider. These tales come from the heart of a North Korean insider. In another poem included with his original hand-written manuscript, he wrote:

I, Bandi, of this so-called world of light

Fated to shine only in a world of darkness,

Denounce in front of the whole world

That light which is truly fathomless darkness,

Black as as a moonless night at the year’s end.

As an insider, Bandi is part of the North Korean Chosun Writer’s League Central Committee, the state-authorized writers’ association. All writers are required to be members. No writer is published, in any format, who is not a member. All members must follow the guidance given by the Department of Propaganda. This means they must be mouthpieces of the state. Drawn to literature and to writing since childhood, Bandi took the only path he had to get his work into print.

The great famine of the mid-1990s, pictures of which were smuggled out and showing up in newspapers worldwide, took many of Bandi’s friends. He started recording the lives of people he knew who died from hunger, social isolation, or tarnished family history.

The contradictions of North Korean society, the land of the loving leader whose people go roaming the countryside for something to eat, determined the course of Bandi’s other, secret writing career. The stories are raw — unpolished, painful, and, yes, well-written, by a writer with an unmistakable and unfairly denied literary life. I wonder what might have been a larger opus for Bandi had he the freedom to read literature of his own choosing and be part of a creative circle.

(What about other writers crammed into the Chosun Writer's League? Did some of them, like Bandi, write poetry and stories since childhood? Could there be a whole generation of silent writers?)

Between two and three million North Koreans died through 1998 from starvation, disease, or sickness caused by lack of food. Hunger is still widespread. The elite in Pyongyang shop at nice supermarkets, but many North Koreans are so hungry that the government has provided recipes for how to cook grass. This is what we should be hearing about in the news, not the present leader's hairstyle (although it is one for comments).

How did Bandi's stories make it out of the country? Like most things that work out the way you want them to, the goddess Fortuna extended herself.

A relative of Bandi's informed him that she intended to flee. Trusting her, he showed her his manuscript and asked her to take it, but she did not because it was too precarious. What if she were caught with it? After many months of preparation, via a circuitous route filled with peril and suspense, she escaped over the border to China, where the Chinese border patrol demanded money from her if she did not want to be sent back.

She promised to get the money. The border patrol's unit commander had heard about a blogger who wrote about North Korean refugees, and he thought this person could help her get it. She met the blogger, who put her in touch with the human rights activist Do Hee-yun.

Do secured her the 10 million North Korean won ($7,500) demanded by the Chinese border patrol, and she was allowed to enter South Korea. Do lost track of her after that, but after months of trying she found him again and she told him about Bandi and his manuscript.

As it happened, Do had a Chinese friend who was traveling to Bandi's town to visit a relative. Do asked this friend to call on Bandi and hand him an explanatory letter, which he did. Bandi trusted him and handed over the mansucript. The Chinese traveler hid it in pieces inside The Selected Works of Kim Il-sung on his return to China. Do eventually got the book to South Korea, where a publisher brought the volume to life.

Mr. Do did not allow any photographs of the manuscript because he feared that someone in the north would be able to identify Bandi's handwriting. He also altered some characters' names and locations as an additional safety measure for Bandi (see Choe Sang-Hun, References).

Writing, Writing, on the Wall

In high school I wondered about what life was like for writers in Stalin's Soviet Union. I hadn't read them by then, they were before my time, but names like Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Boris Pasternak, and others evoked something I couldn't understand, even though I did — the control, harrassment, or imprisonment of smart, thoughtful people, some of the country's best minds. Some were sent to the gulag to be forgotten and to die; many an Ivan Denisovich perished with them.

Anna Akhmatova's (1889-1966) early poetry, for example, was amorous and psychological. As a young woman, she traveled to Paris and enjoyed the life her privileged background afforded her. She was adored by Modigliani, who made sixteen drawings of her in the early 1910s, several of them in the nude.

Fate intervened, of course. She lived through both the Bolshevik revolution and the cataclysmic events occurring in Russia during World War II. She experienced great hunger. Under Stalin (and even earlier), her poetry was banned. Her son Lev Gumilev (1912–1992) was arrested in 1935 after Soviet police found one of Osip Mandelstam’s poems copied in Lev’s hand. In an effort to get him freed, Akhmatova wrote pieces praising Stalin and the “happy life” of the Russian people and denouncing the “lies” disseminated by the West.

It didn’t work. Stalin said she wasn’t sincere enough. Lev was in and out of prison camps until 1956.

Not sincere enough — like some of the tears being wept (and judged) for the departed but never really gone Kim Il-sung or Kim Jong-il. The pseudonym Bandi sounds almost playful, but to me it means courage. Courage I've never had to pull out of myself, courage that stands between freedom and the prison camp, freedom and death.

The North Korean Chosun Writer’s League originally based its rules on the guidelines the Soviet Union set for literature in the 1940s and 1950s, which were that literature is an arm of the state and must conform to nationalistic and political prescriptions.

With Stalin's death in 1953, Kim Il-sung cast off Russian influence and imposed a new prescription for literature, one specifically dedicated to the North Korean ideology of self-reliance and self-defense. The Korean word for this is Juche. This concept of Juche is so important that Kim Il-sung erected a gigantic Juche Tower in Pyongyang, topped with a red flame for eternal dedication. Literature will be created to show a happy land of self-reliant, self-defended people dedicated to their leader Kim Il-sung, the embodiment of Juche. This is still operative, in 2018.

After the division of Korea in 1945, the writer Richard E. Kim, born Kim Eun Kook, fled his home in the north and settled in the south. He was 13 years old. He served in the South Korean army in his country's civil war and emigrated to the United States in 1954, when he was 22. Ten years later he wrote a novel, The Martyred, which got him a Nobel Prize nomination.

Like Akhmatova, his childhood was somewhat privileged, and like her, he endured two separate and brutal political regimes, the Japanese Occupation of Korea and the false liberation of the north, while also witnessing the American and Chinese conflict played out on his soil in the war he fought in.

To understand Korean literature, Kim said, you need to understand the concept of han, the memory of collective trauma that Koreans carry with them in their diaspora:

Han contains a range of human emotions derived from ... awareness of one’s doom ... a sense of loss, doom and destruction; ... one’s sense of being an unfair victim; a fatalistic perception of a fundamentally, inexorably unfair cruel universe; and an equally fatalistic resignation and final acceptance of one’s fate. (see Kim, Plenary Lecture, References)

The doomed characters in The Martyred are North Korean Christians (enemies, to the Communist north) whose God has forsaken them even while they cling to him for mercy. A sense of han consumes their Chaplain, who gives his mightiest sermon to the faithful after realizing his God will not save them. The sermon, an act of love on his part, is all he has for them as their own country sets about to consume them.

Richard Kim died in 2009. He and Bandi both belong to that category of writers called "exiled," although Bandi is an exile inside his own country. Exile, like han, describes the experience of the many millions of displaced Koreans living in other countries all over the world who are still emotionally connected to their homeland. My Korean laundry operator has her Korean news channel on in her shop, every day, all day. When I ask her about the news, she shakes her head. She speaks so quickly I cannot get all of her words.

In Bandi's North Korea, communism is right now losing its ability to sustain both governing and governed, and there is literally nothing to replace it. You're on your own. The government doesn't provide for you like it once may have years ago if you proved your patriotism, but you are still subject to some of the most severe punishment on the planet if you do not follow the empty rules or show enough team spirit.

In a recent online edition of The Chosun Ilbo Daily News from Korea, Kim Soo-hye and Lee Yong-so reported on the trial of six North Korean teenagers, four of whom were sentenced to a year of hard labor for "plotting against the state"; the fate of the other two is not known. All of them were sent to a prison camp after the trial.

Their crime? Apparently, they were listening to South Korean pop songs and dancing. Ten days after this trial, say the reporters, popular South Korean musicians gave concerts in Pyongyang attended by Kim Jong-un. How can a country survive such contradiction and cruelty?

The video below from 2016 is a TED talk given by Joseph Kim, a young man who was once a North Korean orphan, who lost his father to starvation and his mother and sister to disappearance. He escaped to China as a 16-year-old and found help in a refugee sanctuary. His (unfinished) story is one that many ordinary North Koreans, those not protected by status, would not find unusual.

References and Works Cited

Anna Akhmatova, Requiem, an elegy (1961), tr. A.S. Kline, 2005.

Bandi, The Accusation, tr. Deborah Smith (New York: Grove Atlantic, 2017).

Isaiah Berlin, The Arts in Russia Under Stalin, a Memorandum on Literature and the Arts in the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic to Averell Harriman, U.S. ambassador to the U.S.S.R., Autumn 1945.

Choe Sang-Hun, "A Dissident Book Smuggled From North Korea Finds a Global Audience," The New York Times, March 19, 2017.

Anna Fifield, Life Under Kim Jung-un, The Washington Post, Novermber 17, 2017.

Anastasia Ilina, 10 Books That Were Banned in the Soviet Union, Culture Trip, January 5, 2018.

Richard E. Kim, The Martyred (New York: Penguin Books, 1964).

__________, "Plenary lecture," in Chan, M. & Harris, R., eds., Asian Voices in English (Hong Kong University Press, 1991).

Kim Soo-hye & Lee Yong-soo, "N. Korean Teenagers Jailed for Listening to S. Korean Music," April 10, 2018.

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!