What in water did Bloom, waterlover, drawer of water, watercarrier returning to the range, admire? Its universality: its democratic equality and constancy to its nature in seeking its own level ...

—James Joyce, Ulysses, Ithaca, p.671

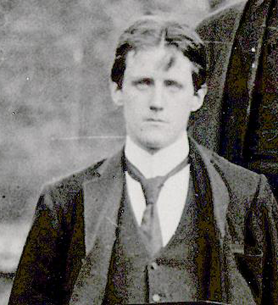

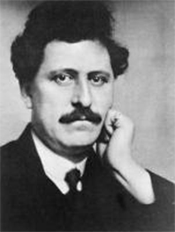

James Joyce, Italo Svevo

& Leopold Bloom

James Joyce's Leopold Bloom is a character at home with reality, and with the mysteries and potential of everyday life. Well-read, fairly cultured but not an intellectual, he excels at experiencing his thoughts and feelings as an activity — not unlike, say, the way a hiker might experience nature and his own sentient thoughts on a trek along the Appalachian Trail.

What else does Bloom admire about water?

...the independence of its units: the variability of states of sea: its hydrostatic quiescence in calm ... the multisecular stability of its primeval basin ... its vast circumterrestrial ahorizontal curve: its secrecy in springs ... its healing virtues: its buoyancy in the waters of the Dead Sea ... its properties for cleansing, quenching thirst and fire, nourishing vegetation: its infallibility as paradigm and paragon... (Ithaca, p.671)

Does Bloom consciously delineate all of this in his mind as Joyce writes it? No, but he senses it experientially and would enjoy his creator's literary rendition of it. Bloom is more interesting, and nicer, than the young Stephen Dedalus, who “distrusted aquacities of thought and language.”

The middle-age Mr. Bloom is comfortable in his own skin, even while handling social slights throughout the day. He is a natural perceiver of the finer and the baser impulses of human nature, including his own nature. His range of thought and feeling as he wanders his city, noticing and processing what surrounds him, his responses internally and externally, are his Ulyssean journey towards home.

A Friendship

Where did Bloom come from? Stephen Dedalus serves as a portrait of the artist as a young man, but Bloom represents something else entirely. After leaving Ireland with Nora Barnacle in 1904 at the age of 22, James Joyce earned a salary teaching English at the Berlitz School first in Zurich and later in Trieste, on the northeast coast of the Italian peninsula, where he and Nora made their home. In 1907, he took on a student 20 years his senior, Italo Svevo, with whom he enjoyed discussions about literature and writing. The two established a lifelong friendship. The highly cultured, well-traveled Svevo was Joyce's inspiration for the person of Leopold Bloom, including Bloom's Jewishness. Joyce admired the strong family ties and moral conscience he saw in his Jewish friends, qualities that describe Joyce himself.

by Mondadori

Aron Ettore Schmitz (Svevo's birth name), born in Trieste in 1861, worked in the family business of manufacturing paint coatings that prevented the build-up of algae and mollusks on ship hulls. His love, however, was literature, and he published two novels at his own expense, Una Vita in 1892 and Senilità in 1898. The books were not successes, and Svevo, who had lacked support of a literary confidant or circle, gave up on writing and decided to increase his English skills for business purposes and also to be better able to read literature in English. With his new young teacher's encouragement he returned to writing. (Joyce himself wrote portions of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and published Dubliners during his time in Trieste.)

By 1923, Joyce was an established figure among the great writers living in Paris. Svevo was still in Trieste when the Bolognese publisher Licinio Cappelli agreed to publish his third novel, La Coscienza di Zeno. The title in English has been translated as Zeno's Conscience, and sometimes as Confessions of Zeno, but the word coscienza in Italian also means consciousness, or awareness. I believe Svevo would agree that Zeno's Consciousness is the better description of his protagonist's mental meanderings and of the book's framework as Zeno's personal journal to review his life. The publication bridged a 25-year hiatus after the completion of Svevo's second novel.

by Capelli

This novel too seemed to go nowhere until Svevo wrote to Joyce, who saw in the percipient protagonist Zeno Cosini a new kind of hero, comic, deeply human, his consciousness flowing upstream from his desires and perceptions. Zeno by turns delights in, is surprised by, and rues the motives for his own and others' actions; he is predictable and imperfect, but kindly. Joyce shared the book with the critics Valery Larbaud and Benjamin Cremieux, who translated it into French and had it published to acclaim, and a grateful Italo Svevo assumed his life as a European novelist. He is now celebrated in Trieste, where the Museo Sveviano provides a trove of information on its native son and hosts lectures and events throughout the year.

Watercarrier Returning

I do not like the cartoon-like drawings various people have made of what Leopold Bloom may have looked like, even the one Joyce himself drew (Joyce admitted that he could not draw and that his taste in art was unsophisticated.). So I include here a picture of the Svevo that Joyce knew, to give some depth and breath to the character and thoughtfulness of Leopold Bloom. I also like the sketch (below) of Bloom by the British artist Richard Hamilton from his Imagining Ulysses series housed in London at the Tate Gallery. When asked, Joyce said Bloom might look like the British journalist, writer, and publisher Holbrook Jackson, also shown below.

downloading of image prohibited without written permission of ARS of New York.

Like Svevo's protagonist, Bloom is both introspective and an ordinary guy, but unlike Zeno Cosini, he is, as Joyce's title presumes, heroic. What makes Bloom a hero? His odyssey doesn't take him to strange lands or confront him with otherworldly challenges. Joyce's conception of art was grounded in life. He had little taste for the Celtic mythology revival in his homeland (as important as that was in the emergence of a free Ireland). Ordinary life is already a vessel for extraordinary challenges, surprises, and sublime joy, but you must pay close attention sometimes to notice. We in our modern American culture seem constantly to be on the lookout for the new and different, often blind to what is in front of us because we're looking past it. Bloom looks straight at it, as does Stephen Dedalus. They are agents of freedom (and artistic freedom) because they process what they see and feel and come out renewed.

Critics have had their way with Mr. Bloom. Harry Levin, in James Joyce: A Critical Introduction, calls Bloom “the complete misfit of all literature.” He is “the apotheosis of those blighted types that Joyce sketched in Dubliners." But if this were true, Ulysses would not be comic, or tragic, or would not even make sense.

Joyce told his friend Frank Budgen that he received a letter asking him to give Bloom a rest. “The writer wants more Stephen. But Stephen no longer interests me to the same extent. He has a shape that can’t be changed,” Joyce said. Bloom is protean. Far from being the blighted Dubliner, the museful Mr. Bloom comes out on the other side of uncivil and deadening encounters still generous in his thoughts. He seeks life.

Sylvia Beach, the American proprietor of the Parisian bookshop and lending library Shakespeare and Company, was the original publisher of Ulysses. In 1956, in a New Year's greeting to friends published as the small volume Ulysses in Paris, she reminisced of her friend James Joyce:

Joyce's effort to be a good family man and respectable bourgeois ..., a role so little befitting the "Artist" of The Portrait, was very touching. And it helped you to understand Ulysses. It is so interesting to see how Stephen recedes and grows dimmer, while Bloom emerges and stands out clearer and clearer, finally taking over the whole show. I felt that Joyce fast lost interest in Stephen and that it was Mr. Bloom who had come between them. After all, there was a good deal of Bloom in Joyce. (Beach, p.19)

Joyce told Frank Budgen why he chose Odysseus as the prototype for his hero. Christ was a bachelor, Faust was plagued by Mephistofeles —where are his home and family? Odysseus is son to Laertes, father to Telemachus, husband to Penelope, lover of Calypso, companion-in-arms to Greek warriors, a war dodger, and a plougher of the fields. And he is resilient.

The Wandering Irishman

Like Odysseus, Mr. Bloom's journey starts with Telemachus and continues through every episode of Homer’s poem to finish with Ithaca and Penelope at No. 7 Eccles Street. But Bloom's substrate is as Jewish as it is Ulyssean. He is also Irish at a time Irish Catholics lived under restrictions sometimes more severe than those placed on Jews; in their own land, Catholics could not become professionals or serve as statesmen; the doors of Trinity College, Dublin, where I once spent a summer learning Irish history, were never open to Joyce; Catholics, like Jews, were shop owners, small businessmen, employees, or if they were rural, farmers. Bloom, the Wandering Jew, was realized by Joyce, the Wandering Irishman, also seeking home, who found it in art and, more directly, his own art, and in the people who nourished his life and his art.

Bloom’s encounters throughout the day continuously bring him back to his Jewish roots and memories. In Aeolus he stops into the newsroom to sell the Keyes ad, the symbolism of which suggests Irish home-rule, the current political antagonism. Then he notices a typesetter reading the newsprint backwards and thinks:

Poor papa with his hagadah book, reading backwards with his finger to me. Pessach. Next year in Jerusalem. Dear, O dear! All that long business about that brought us out of the land of Egypt and into the house of bondage Alleluia. Shema Israel Adonai Elohenu. No, that's the other. (Aeolus, p.122)

He catches himself—his Hebrew isn't quite right, and he knows that. Joyce’s European Jewish friends were assimilated, many like Svevo converted to Christianity as they married outside of their religion, but like Bloom they never really lost their Jewishness, in good part because the greater society constantly reminded them of it (These were years leading up to, and during Joyce's writing of Finnegan's Wake including, the Nazi occupation of Europe.). Cultured and assimilated as they were, they were exiled in their own countries, and Bloom also feels it directly at times, notably in his encounter with the nameless citizen in the Cyclops episode.

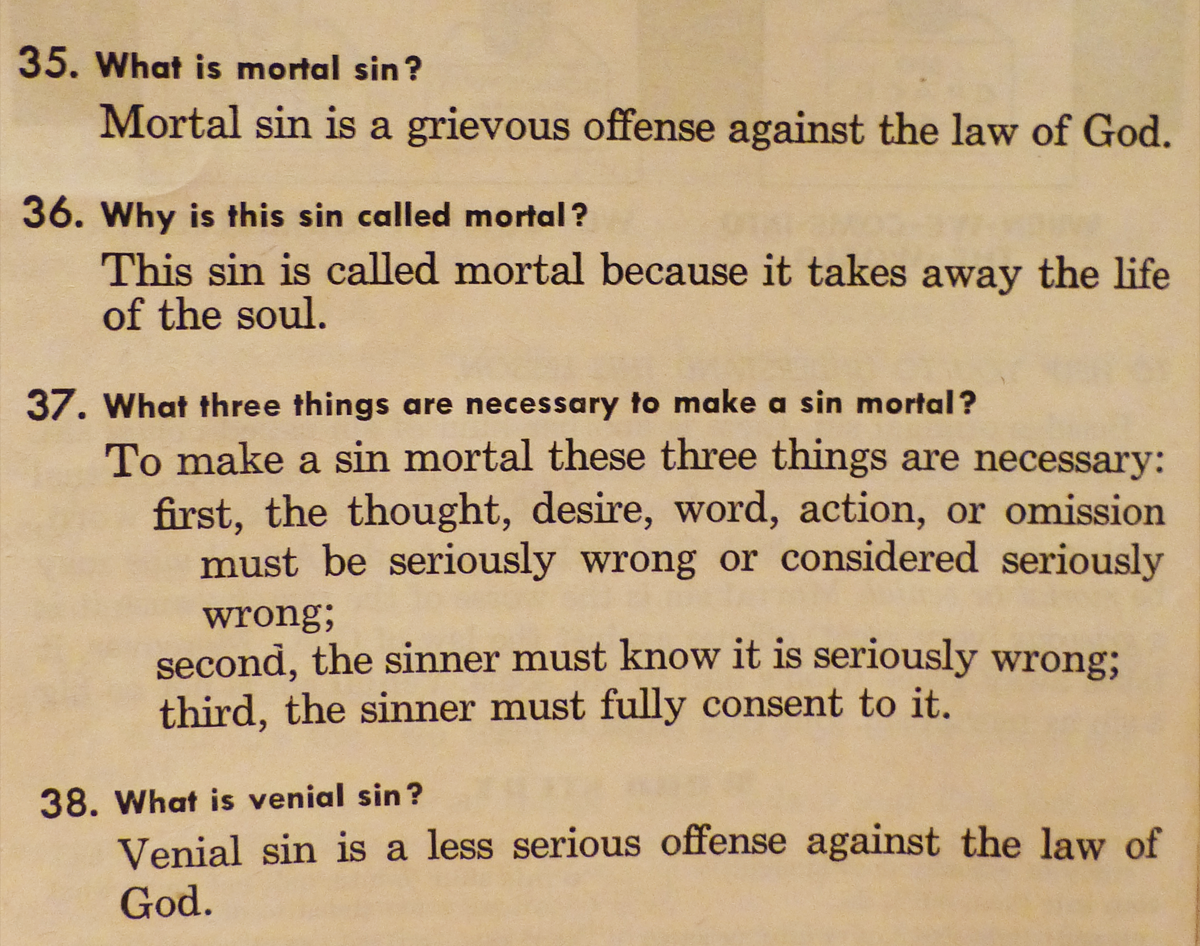

Ulysses is also suffused with Joyce’s classical Roman Catholicism. The book begins with Buck Mulligan's intonation of the Catholic Mass: Introibo ad altare Dei (I go to the altar of God). Bloom later attends Mass; and in Hades he is at Dignam’s funeral Mass. The question-and-answer structure of Ithaca, my favorite chapter and the final chapter before Molly’s soliloquy, is taken entirely from the Baltimore Catechism (first compiled in 1832), the official Catholic School study guide that I memorized in grade school, which uses a question-and-answer format to explain the nature of God, sin, the ten commandments, the sacraments, transubstantiation, and other sacred beliefs.

Photograph by Frances Stevens

jewgreek & greekjew

What does all this mean? Critics and reviewers have fittingly applied various mythical, literary-historical, Freudian, and other points of view to Joyce's Ulysses. But Joyce himself has given us Blephen-Stoom, jewgreek and greekjew. Joyce liked the great English poet and writer Matthew Arnold’s 1868 essay, “Hebraism and Hellenism,” in which he discusses what he believes are the two life forces that mold the European. Hellenists are at ease in the world, Arnold says, while Hebraists (which include Christians) find it impossible to be at ease in the world, and we straddle these forces:

The discipline of the Old Testament may be summed up as a discipline teaching us to abhor and flee from sin; the discipline of the New Testament, as a discipline teaching us to die to it. As Hellenism speaks of thinking clearly, seeing things in their essence and beauty, as a grand and precious feat for man to achieve, so Hebraism speaks of becoming conscious of sin ...

Hebraism and Hellenism are, neither of them, the law of human development ... they are, each of them, contributions to human development … (Arnold, Ch.4)

Library of Congress

(Arnold forgot the fairies. Before Hellenism and Hebraism there was the flock of European fairies, elves, witches, imps, giants, shape-shifters, ogres, and helpers who live still at crossroads, in the mountains, underground, under the bed, and in streams and forests from Norway to Eastern Europe, in palpable shadow.)

Stephen Dedalus (Hellene) and Leopold Bloom (Hebrew) focus on reality, as it presents itself to them. Stephen’s ideas about artistic creation, and Bloom’s unswerving compassion, come from their deep humanity. The person of Bloom, gifted in his sense of right and wrong, provides the connective tissue to the “themes” present in this book—paternity, the cyclicality of life, the universal in the particular, the transcendent power of art and love.

Bloom's strength comes alive in the Cyclops episode. In the Greek epic, Odysseus must fight his way out of the cave of the cannibalistic, one-eyed cyclops. For Bloom the cave is Barney Kiernan's Pub, with its obstreperous narrator and its obstreperous citizen, both nameless. Bloom had planned to meet Martin Cunningham at the pub at 5 p.m. and then accompany him to the Dignam home to help the mourning family understand Paddy’s life insurance policy. But Bloom gets trapped in a mean-spirited discussion with the citizen and fights his way out by defending tolerance, as a discussion of Irish nationalism ensues.

—What is your nation if I may ask? says the citizen.

—Ireland, says Bloom. I was born here. Ireland. (Cyclops, p.331)

For the citizen, everything Irish is good and honorable. He’s from an oppressed race! Everything not Irish, especially English (and on a more insidious level Jewish) is intolerable. (Ironically he’s not as honorable as he puts on because he bought out the property of an evicted tenant.) Bloom answers him:

—And I belong to a race too, says Bloom, that is hated and persecuted. Also now. This very moment. This very instant.

...

—I'm talking about injustice, says Bloom.

—Right, says John Wyse. Stand up to it then with force like men.

...

Old lardyface standing up to the business end of a gun. Gob, he'd adorn a sweepingbrush, so he would, if he only had a nurse's apron on him.

...

—Force, hatred, history, all that. That's not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it's the very opposite of that that is really life.

—What? says Alf.

—Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred. I must go now, says he to John Wyse.

...

—A new apostle to the gentiles, says the citizen. Universal love.

—Well, says John Wyse. Isn't that what we're told. Love your neighbour.

—That chap? says the citizen. Beggar my neighbour is his motto. Love, moya! (Cyclops, p.332)

The Cyclops cave is an entrapment in space and time, here Dublin in the early 20th century, as Ireland begins its lonely fight for home rule. The eye the cyclops are missing is the one that sees their connection to Bloom as natural. Their aggression toward him masks a covert admiration. Joyce’s Dubliners suffer religious and political repression, and indeed oppression, keeping them from living up to their potential. Bloom is one man who is not a denying power in their lives. Unthreatening in his nature, he is the one person they can vent their frustration on without fear of counter threat.

Ithaca at No.7 Eccles Street

I love that Leopold Bloom lives on Eccles Street (a fine Dublin address at the time with elegant Georgian townhouses). Eccles, of course, comes from the Greek ecclesia, meaning church. How Joyce played with words! On a return trip to Dublin in August 1909 with his four-year-old son Giorgio, Joyce visited his friend John Francis Byrne, who actually lived on Eccles Street, at No. 7 (see photo below). The house becomes Bloom's, where on June 16, 1904, Stephen partakes in a remarkable back-and-forth discussion with him, during which art, humor, and interesting and original ideas get tossed and connected into the wee hours of the morning.

What two temperaments did they individually represent?

The scientific. The artistic. (Ithaca, p.683)

In the kitchen on Eccles Street, two mortal temperaments, considered by many to be opposites, find they have common aspirations. Their two minds wander through the same terrains, thinking differently. Bloom seeks to understand the world through the physical laws of nature, with his unsophisticated speculation on the parallels of natural cycles, history, and the universe. Stephen, for whom history is, in his famous phrase, “a nightmare from which I am trying to awake” (Nestor episode, p.34), needs to connect through art. Mr. Bloom gently admires the intellectual powers he ascribes to Stephen, but knows that his own instincts are more practical.

Language, History, All That. Ithaca sets out the collisions and parallels Joyce creates between his culture and the Jewish culture he adopted for his hero. When I played a YouTube video for my husband of an interview with the modern Irish composer Peadar Ó Riada conducted in Gaelic, he said, “That sounds Arabic." Well, here is Blephen-Stoom on the matter, with Joyce's ever present joy of words (not to mention wit and humor), and with the two characters' mutual respect for the richness of their cultures and their associated humiliations:

What fragments of verse from the ancient Hebrew and ancient Irish languages were cited with modulations of voice and translation of texts by guest to host and by host to guest?

By Stephen: suil, suil, suil arún, suil go siocair agus suil go cuin (walk, walk, walk your way, walk in safety, walk with care).

By Bloom: Kifeloch, harimon rakatejch m'baad l'zamatejch (thy temple amid thy hair is as a slice of pomegranate).

...

Was the knowledge possessed by both of each of these languages, the extinct and the revived, theoretical or practical?

Theoretical, being confined to certain grammatical rules of accidence and syntax and practically excluding vocabulary.

What points of contact existed between these languages and between the peoples who spoke them?

The presence of guttural sounds, diadritic aspirations, epenthetic and servile letters in both languages: their antiquity, both having been taught on the plain of Sinar 242 years after the deluge in the seminary instituted by Fenius Farsaigh, descendant of Noah, progenitor of Ireland: their archaeological, genealogical, hagiographical, exegetical, homiletic, toponomastic, historical and religious literatures comprising the works of rabbis and culdees, Torah, Talmud (Mischna and Ghemara), Massor, Pentateuch, Book of the Dun Cow, Book of Ballymote, Garland of Howth, Book of Kells: their dispersal, persecution, survival and revival: the isolation of their synagogical and ecclesiastical rites in ghetto (S. Mary’s Abbey) and masshouse (Adam and Eve’s tavern): the proscription of their national costumes in penal laws and Jewish dress acts: the restoration in Chanah David of Zion and the possibility of Irish political autonomy or devolution. (Ithaca, p.688)

Understand that this is art speaking. Italo Svevo taught his ever-curious English teacher everything he knew about Jewish culture, rites, and sacred texts by the time he left Trieste. And maybe Joyce was on to something. I took the picture below from an old Irish Grammar book I have. The page shows a declension of the noun king. The characters are modern Irish, but they are not evolved from Western languages. The scholar R.L. Thompson noted in his book Outline of Manx Language and Literature that Gaelic syntax "has similarities with that of languages like Hebrew and Arabic.”

(The Irish phrase Stephen speaks in the quote above is from an old Irish love song called Siul arún, of which a rendition by Clannad can be heard on YouTube, in English and Irish. Joyce was known to have a beautiful tenor voice and played piano and guitar and composed songs. Siul arún was probably a favorite of his, as he has Stephen recite some of it in Bloom's kitchen.)

Molly Bloom pervades the pages of Ulysses as a prototype of Anna Livia Plurabelle, the soul and center of Bloom’s universe, the one he returns to in his thoughts throughout the day. She streams through Bloom's consciousness, as Anna Livia streams through the center of the moving labyrinth of Dublin—the Liffey River, baptismal font of the city, life force. Joyce named Anna Livia Plurabelle after Svevo’s wife Livia Veneziani. I’m sure he loved the Liffey-Livia consonance and assonance. She, however, was unimpressed that Joyce placed Irish washerwomen along its banks!

Although we get to know Mr. Bloom intimately, seeing him through his own eyes, his wife’s, and those of several Dubliners, down to the contents of his bedroom drawers, he's still a mystery. We don't really unlock the secrets of his eating habits (he relishes “the inner organs” of animals), the door to the ghost of his dead son Rudy, or the origins of his wide interests.

He’s not an “everyman”; he’s exceptional, with an unassuming goodness on the human level and “a touch of the artist” on the imaginative level. He enjoys fiction, science, drama, music, history. His compassion comes through in the little things he does on that June day in 1904: his sympathetic talk with Mrs. Breen, his concern for Mrs. Purefoy, helping the Dignams, worry for Stephen’s sister Dilly, his thoughts on student politics, his almost motherly care for Stephen.

Trieste

Bloom not only shares a history with Molly, he is the “transubstantial heir of Rudolf Virag (subsequently Rudolph Bloom) of Szombathely, Vienna, Budapest, Milan, London and Dublin.” His father was the Hebraic easterner migrating westward, with a gaze that went, like Bloom’s, both ways. Italo Svevo died in 1928, a passenger in a car accident. In a lecture he gave in Milan in 1927, translated from the Italian by Joyce's brother Stanislaus (and first published by New Directions in 1950) as the short volume James Joyce, Svevo said:

[W]e Triestines have a right to regard him with deep affection as if he belonged in a certain sense to us. ... It is a great title of honor for my city that in Ulysses some of the streets of Dublin stretch on and on into the windings of old Trieste. Recently Joyce wrote to me, "If Anna Livia (the Liffey) were not swallowed up by the ocean, she would certainly debouch into the Canal Grande of Trieste." ... Trieste was for him a little Ireland which he was able to contemplate with more detachment than he could his own country.

...

Joyce's outward life at Trieste could be summed up as a spirited struggle to support his family. His inner life was complex but already clear-cut: the elaboration of the subject matter offered him by his childhood and youth. A piece of Ireland was ripening under our sun. (Svevo, Sec.3a)

Of the meeting of Bloom and Stephen on Eccles St., Svevo writes:

At the close of a memorable day the scholar Dedalus comes to the point of feeling the Jew Bloom to be a kind of father to him, while Bloom for his part, amid dreams and adventures, is also aware of a sense of fatherhood. The incident is plausible because Bloom has lost his son, and Stephen would like to find some substitute for his own living father, whose tenor of life is enough to explain Stephen's mood of despair. The approach is rendered possible by other reasons. The Jewish and Irish are both nations whose languages are dead. Stephen, moreover, is attracted by one who is very far from his own way of thinking, and feels a relief in communion with one who eschews all the culture that obsesses Stephen. (Svevo, Sec.3a)

Svevo had this to say about their thought processes:

Bloom and Stephen communicate directly with the reader, their solitary thoughts taking the form of a monologue. They walk about with their brain-pans uncovered. (Svevo, Sec.3a)

In her Memoir of Italo Svevo, Livia Veneziani reproduces, among other things, the letters between Svevo and the French critics Larbaud and Cremieux in the early years of Svevo's renewed literary career. She was the protector of his manuscripts and correspondence, especially after his death, having written her memoirs in hiding during the later years of World War II, with two grandchildren missing in Russia and one killed during the liberation of Trieste.

Ira Nadel, in his book Joyce and the Jews, talks about the effect of the second world war on Joyce, who was in hiding first in Vichy and later in Zurich, where he died in 1941. Joyce worked to successfully secure passage out of Europe for some of his Jewish friends. I was saddened to read in Nadel's book of the fate of Paul Léon who, Nadel says, was a part of every significant literary event involving Joyce between 1929 and 1940. Léon was a Russian Jewish emigre to Paris, highly skilled in languages and classics, and Joyce came to depend on him for his editorial advice. Léon oversaw the translation of Finnegan's Wake into French and was responsible for saving Joyce's library by giving his important papers to the Irish ambassador to occupied France, to deposit into the National Library of Ireland. On August 21, 1941, the Gestapo arrested Paul Léon and he was later murdered in a German concentration camp in Silesia.

The Triestine legacy of both Svevo and Joyce continues to grow. In addition to the Museo Sveviano, Trieste in 2004 opened the Museo Joyce, which houses original editions and important Joyce memorabilia. A short YouTube video, James Joyce's Ulysses Documentary, gives a good overview of it. The two statues below by the Triestine sculptor Nino Spagnoli were also erected in 2004, of Svevo in the Piazza Hortis on his way to the Library, and of Joyce looking out over the bridge of the city's Grand Canal.

Courtesy of Giampiero Campajola, Founder, Trieste Racconta.

The connection between Mr. Bloom and Mr. Svevo is real and to me interesting and even riveting, but this connection hardly rounds out the puzzle of Ulysses. Some critics think of Joyce's work as a kind of secular, or literary, bible, and as with the Bible, interpreters find in it what they want. But I don't think Joyce would necessarily agree.

The thing is, there is so much of Joyce himself in his work. When Svevo says that Stephen and Bloom "walk about with their brain-pans uncovered," he is talking about Joyce, who laid bare his entire self to his writing and to those who worked closely with him. Joyce's person and the facts and circumstances of his life are compelling. His advisor and helper Paul Léon, at the age of 20 and while still in Russia, wrote a legal thesis on, of all things, Irish Home Rule, the process of which was of great interest to Joyce, even though he was not overtly political (see Nadel, p.227). Joyce's genius, the convergences of the people and events in his life, and the background of history all round out Ulysses, and they are indeed complex.

Works Cited

Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy, Ch. 4, "Hebraism and Hellenism" (University of Adelaide, eBooks@Adelaide, 2015. First published 1869 by Smith, Elder & Co).

The New Baltimore Catechism (Benziger Brothers, Inc., 1949).

Sylvia Beach, Ulysses in Paris (Harcourt Brace & Co. private printing, 1956).

Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of "Ulysses" (Oxford University Press, 1972).

The Christian Brothers, Irish Grammar (Dublin: M.H. Gill & Sons, Ltd., 1904).

James Joyce, Ulysses (The Modern Library, 1961).

Harry Levin, James Joyce (New Directions Books, 1941).

Ira Nadel, Joyce and the Jews (University Press of Florida, 1996).

R.L. Thomson, Outline of Manx Language and Literature (Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh, 1988).

Italo Svevo, La Conscienza di Zeno (Bologna, A. Capelli, 1923);

Confessions of Zeno (Vintage International Books, 1989);

James Joyce, tr. Stanislaus Joyce (City Lights Books, 1969).

Livia Veneziani Svevo, Memoir of Italo Svevo, tr. Isabel Quigly (Marlboro Press/Northwestern University Press, 1990) (originally published in 1950 by Edizioni dello Zibaldone, Trieste).

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!