Medieval Mindfulness:

Bokes enlumyned ben þey

It’s a fact that when I see something medieval, I probably like it. Not that I don’t like other periods; I do, but medieval representations and accounts have a tactile earthiness and simplicity that aren't as available in these virtual days. There's more to it, though, it only looks simple.

It’s weird to hear people describe the European early middle ages as “the dark ages” — when nothing happened for hundreds of years (300 to 1100? I don’t know.). Europe was actually wildly afoot with merging and clashing cultures, mass migrations in every direction, uprooted peoples trying to make sense of the world, no longer knowing what to call themselves.

In the fourth century, rich young Romans were giving their parents apoplexy by forsaking their inheritances for a life of austerity and Christian meditation in the North African desert. In her book The Desert Fathers, Helen Waddell gives poignant descriptions of the life of these "athletes of God," as the desert dwellers came to be called. "Tell me ... If new roofs be risen in the ancient cities: Whose empire is it now that sways the world?" asked the desert father Antony of St. Jerome (Waddell, p.14, quoting Jerome).

Their life style added nothing of substance to the religious canon, Waddell writes, but their actions "showed a standard of values that turned the world upsidedown" (Waddell, p.22):

The one intellectual concept they did give to Europe: eternity. . . . These men, by the very exaggeration of their lives, stamped infinity on the imagination of the West. . . . "The spaces of our human life set over against eternity" — it is the undercurrent of all Antony's thought — "are most brief and poor." (Waddell, p.23, quoting Antony)

In 345, Irish monks were sailing to Iceland for a little peace and quiet to write the new gospels, having sailed the Atlantic route to Italy to pick them up from Jerome, among others. The lure of quietude, humility, a new search for meaning, took over the imagination of many.

Used by permission.

Merovingians & Carolingians

A little later, the Merovingians, a Germanic people known as the long-haired warriors whose Scythian tribal forebears came from the Eurasian Caucuses, migrated into France and established the Frankish dynasty in all areas except that which we call Provence. They came with a rich tapestry of deities and myths, not Greek or Roman or Middle Eastern. Under their leader Clovis, who in 496 had himself baptised in the Christian faith, they too became Chrisitanized.

Carolingians replaced these people in the 700s; their famous leader Charlemagne admired and desired all of the culture of ancient Rome so much that on December 26 in the year 800, he had Pope Leo III crown him the first holy Roman emperor.

Charlemagne sent emissaries around Europe to find out what was happening, language-wise, and they came back to report to him the differences between Spanish, Italian & French. The source language, Latin, became the language of the ruling and learned classes throughout Europe.

Emergent English

In 731, the monk Bede (672-735) wrote, in Latin, A History of the English People, which covered the Anglo-Saxon migrations into the Romano-British isle of Albion starting in 450 AD, when the Romans retreated and the native island people no longer had a military presence to protect them. A translation of Bede's history is available online.

Bede was the first person officially to call the people on the island "English" (gens Anglorum). In the late 800s or very early 900s, a translator in King Alfred's court translated Bede's popular work into the vernacular, that is, Old English. Alfred, a literate and educated man, wanted to raise the level of literacy in his country so that ordinary people would be able to read and recite important works in their own language. He started the translation program for this purpose. The sample below of the translation of Bede begins his discussion of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of the island:

Comon hi of þrim folcum þam strengestan Germanie, þæt is of Seaxum & of Angle & of Geatum. Of Geata fruman syndon Cantware & Wihtsætan þæt is seo þeod þe Wiht þæt ealond oneardaþ. Of Seaxum, þæt is, of þam lande þe mon hateþ Ealdseaxan, coman Eastseaxan & Suþseaxan & Westseaxan. And of Engle coman Eastengle & Middelengle & Myrce & eall Norþembra cynn; . . .

Translation

They came from the three strongest peoples of Germany, that is from the Saxons and the Angles and from the Jutes. Of Jutish origins are the people of Kent and the residents of Wight, that is, the nation that inhabits the island of Wight. From the Saxons, that is, from the land that one calls Old Saxony, came the East Saxons and the South Saxons and the West Saxons. From the Anglia came the East Angles and Middle Angles and Mercians and all the Northumbrian tribe; . . .

And they came from Scandinavia. They developed a technically alliterative writing style that became the standard of excellence in Old English poetry. Beowulf, the bane of every American high school sophomore, was written in the late 700s in England, in Old English, but it was about life in Sweden in 500. And that life was a hard one, with uncertain rewards for the hard work. Hwæt, the opening word of Beowulf, means Listen [or, Hear what]! The story was recited for centuries before the Beowulf poet wrote it down.

Ireland

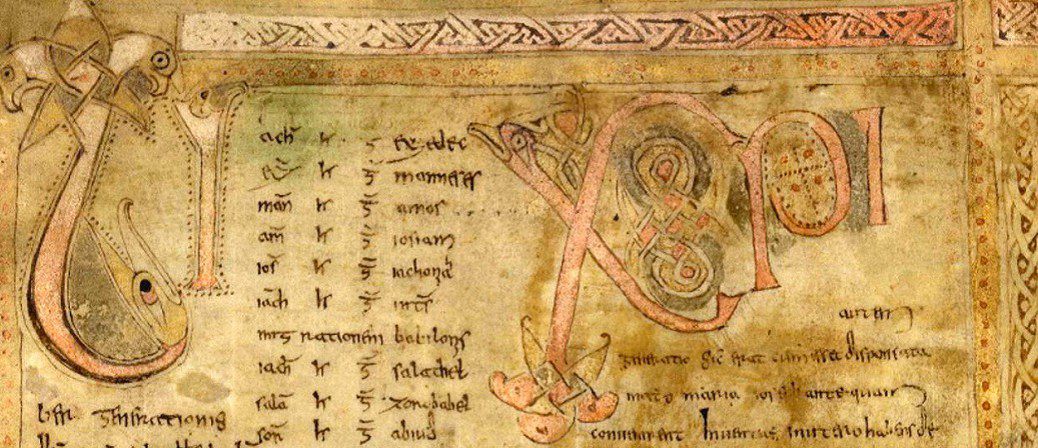

A June 1, 2017 headline from the Trinity College, Dublin, news and events website page has the headline, Trinity unveils precious Irish manuscripts from the "Dark Ages" (quotation marks are mine). Trinity should know better than to use the term! Ireland has a number of manuscripts from the fourth to seventh centuries created before the artistic explosion that came in the eighth century with the Book of Kells (below).

The island suffered neither Roman nor Anglo-Saxon invasions (save one raid in 684 on County Meath, which Bede in his History called an "unwarranted attack"). The Irish oral tradition was very old by the time the monks adopted Latin in 431. Stories written in Irish are the oldest vernacular literature in western Europe. Wikipedia has a nice summary of early Irish writing.

Trinity College Dublin.

One manuscript on parchment from the fifth century, the Codex Usserianius Primus, or First Book of Ussher (right), is an incomplete compilation of gospel stories. Scholars haven't decided whether it was started in Ireland or on the continent, but the scribes annotated — wrote personal comments on — the pages in Old Irish. Irish scribes continued this habit for centuries, giving modern translators some access into their lives and thoughts. I found this small but very good image of Irish annotation in the margins and between the lines of text (but I do not know which manuscript the image is from).

The pagan Irish myths lived alongside the new religion with seeming affinity. The Book of the Dun Cow, written in Irish circa 1070 by Máel Muire mac Céilechair, of the monastery of Clonmacnoise in County Offaly, contains Irish myths, factual stories, Irish history, and gospels. The manuscript (part-page below) contains the famous myth of The Cattle Raid of Cooley. Is is online in its entirety, in Irish.

The Golden Age of Spain

Meanwhile, in southern Spain in 700, newly arrived Arab invaders/migrants crossing from North Africa established a caliphate and created a culture so rich, it lasted for centuries and eventually became a threat to northern kingdoms. By the 800s, the culture of al-Andalus ("becomes green at summer's end"), or Andalusia, more resembled Baghdad than the cultures north of the Pyrenees.

Mozarabic Spain (Almeria, Córdoba, Granada, Jaen, Seville, Toledo, etc.) became a full-fledged melting pot for Mediterranean, Persian, and Middle Eastern cultures. Here, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars, all of whom found a welcome, worked in tandem, translating the rediscovered science, philosophy, history, and literature manuscripts of the ancient Romans and Greeks into Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew.

Córdoba was the birthplace of both Moses Maimonides (Moshé ben Maimón, Jewish scholar, physician, and author of Guide to the Perplexed) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd, Muslim philosopher, jurist, and physician). Toledo, a major educational center, had a multicultural atmosphere that fostered a freedom to debate and disseminate new ideas. It was Muslim Spain that hosted the Jewish Golden Age.

By 1100, the Arab Muslims and Jews of Andalusia, scholars of the sky, had mastered the astrolabe that was coveted by the English kings (like Henry II of England, 1133-1189, who sought out Arabic astronomers). Using the mathematical principle of stereographic projection (a way to map a sphere onto a plane) as described by Hipparchus of Nicaea (Greek, 150 BC), they made functional instruments of great beauty. (If you are curious about how the astrolabe works, go to The Astrolabe. This site is thorough, in a user-friendly way, with pages on the types, components, design, and other interesting facts about the instruments.)

The medieval brass astrolabes are recognized as world-class works of art. They are a testament to our quest for knowledge and the retention of knowledge. Josefina Rodriguez-Arribas, a scholar of medieval science and astronomy, said of the astrolabes, "They are one of the most sophisticated instruments ever constructed before the invention of the computer” (Rodriguez-Arribas, References).

All rights reserved.

In my graduate school years in the mid-1970s I took a summer course at Oxford University, England, in medieval astronomy with John North, a professor of the history of science. Our little group studied the astrolabes, visited Stonehenge, discussed Chaucer's use of astronomical allusions in his poetry, and gazed at the stars on the college's lawn at night. We had tea with Mr. North's wife Marion and some visiting Australian astronomers in his home. A true scholar and one of the nicest people I've ever known, Mr. North proved that Stonehenge's purpose was for observation of the setting of the midwinter sun, not the rising of the midsummer sun.

From Mr. North I learned that the poet of the Canterbury Tales was an amateur astronomer who studied astrolabes with enduring interest. Geoffrey Chaucer wrote the first technical treatise on the astrolabe in the English language, and dedicated the treatise to his son Lewis.

Little Lewis, my son, I see some evidence that you have the ability to learn science, number and proportions, and I recognize your special desire to learn about the astrolabe. So ... I propose to teach you some facts about the instrument with this treatise.

—Geoffrey Chaucer, A Treatise on the Astrolabe, circa 1390

While at Oxford, John North was an assistant curator from 1968 to 1977 at the Museum of the History of Science. Later, from 2003 to 2008, he was a senior research associate at the museum. The first six astrolabes in the slideshow below are from the Oxford museum's collection, where we spent time in study. The last two images I took recently at a museum show in Manhattan.

While authors like Bede's translator in Alfred's court self-consciously wrote in English instead of Latin, determined to make English a language of science, philosophy, and art, writers in Andalusia were busy creating new poetic styles.

Sufi Arabs (followers of a mystic branch of Islam), fleeing a more repressive home country in the Middle East, found open eyes and ears in Andalusia, where they created the technical language and format for a new devotional poetry, the zagal. From the zagal evolved the ghazal, the secular courtly love lyric that became wildly popular and the basis for poetry contests of the Spanish courts.

In time, songwriters from France (troubadours) crossed over the Pyrenees to compete in these poetry contests. The troubadours had to prove not only their literary prowess but their knowledge of music — the bagpipes, rebecs, viols, pipes, flutes, drums, lutes & lyres that accompanied their verses. The competitors were Arabic, Jewish and Christian, but the contests were far from religious. Sephardic (Spanish Jewish) love songs were numerous and popular. The video below is of the love song Avrix mi galanica, a very popular song at the time. As it translates:

Open [the door] my beauty / for the dawn is near.

I will open / my sweet love,

for at night I don't sleep / thinking of you.

My father is reading / he'll hear us.

Take away his glasses / he'll fall asleep.

My brother is writing / he'll hear us.

Take away his pen / he'll fall asleep.

My mother is cooking / she'll hear us.

Take away her ladle / she'll fall asleep. (tr. © Gerard Edery)

What about those bagpipes, rebecs & lyres? I've always loved the drone sound in early European music, but it's been mysterious to me, as the drone is Indian (and still exists in the music there). Still, from whatever medieval European court, the sounds are similar, the drone is there, and the sound is very old. In the short video below, a musician plays a piece from about 1150 on a crwth, a Welsh form of lyre.

Over time the contests migrated into the courts of France, Italy, Germany and England.

Ibn Quzman (1078–1160) of Córdoba, the most famous courtly poet of his time, was a gifted crowd pleaser and a braggart. To him, love was a poem well-executed and he was the greatest lover because his verses were the best. Try to win a contest with him! His poems have all the characters, drama, states of mind, causes and effects of love, and distinctions between false and true love that became the staple diet of the French troubadours (see Nykl, p.269). Quzman's verses fulfilled prescribed technical formulas and his sophisticated audiences could understand his word play, levels of meaning, and metaphors, which could be ribald. The video below of one of his songs is a tribute to Quzman.

Another comely and popular Arabic love song was Las Tres Morillas. In the video following this translation, Jordi Savall plays a beautiful rendition on his viol:

I am in love with three Moorish girls in Jaen,

Axa, Fatima, and Merien.

Three Moorish beauties / were going to pick olives,

and found them already picked in Jaen,

Axa, Fatima, and Merien.

And they found them picked / and returned disheartened

and pale of color in Jaen,

Axa, Fatima, and Merien.

I said to them, "Who are you ladies

who have captured my heart?"

"Christians, though once we were Moors / from Jaen,

Axa, Fatima, and Merien."

With their great beauty, / manners, wit and good sense

they sealed my fate and fortune,

Axa, Fatima, and Merien.

Three alluring Moorish girls / went to pick apples in Jaen,

Axa, Fatima, and Merien. (tr. © Gerard Edery)

The beloved Italian Renaissance, birthplace of the modern era, actually began in the 900s in Andalusia, Spain. There, translators and scholars, scientists and physicians, artists and architects, musicians and poets, had freedom to explore and create. They were free of certain religious and traditional restraints, and life was good. It was the Spanish Inquisition of 1492 that drove the Renaissance into Italy, through Sicily and up the Italian peninsula.

It's hard to think about. Spain wanted a Christian prestige like the northern countries. It lost its heart and mind, entered a dark period, after having hosted one of Europe's most promising.

The Age of Alliteration

We prefer our time. We certainly have no interest in going back to 350, or 700, or 1100, or 1492. We've had the Enlightenment, the Declaration of Independence, and the Age of Technology, with its 10-second attention span, is now upon us. But that doesn't mean it's okay to dismiss several hundred years of our cultural past, throw them into a bin marked "dark ages."

Of course, life in medieval times differed greatly depending on where you lived, and those differences could be formidable.

But it is also true that early medieval European art, literature, philosophy, and science shared a similar trajectory, that their creators were on a search for understanding our life in this universe. Sifting through what remains, I am astonished at the work itself. It makes you think; it requires a mental presence, or mindfulness (sometimes, hard work), to experience as it was experienced long ago. People were always thinking and judging, we certainly didn't invent these mental processes.

On Piers, a Plowman & the Joy of Riddles

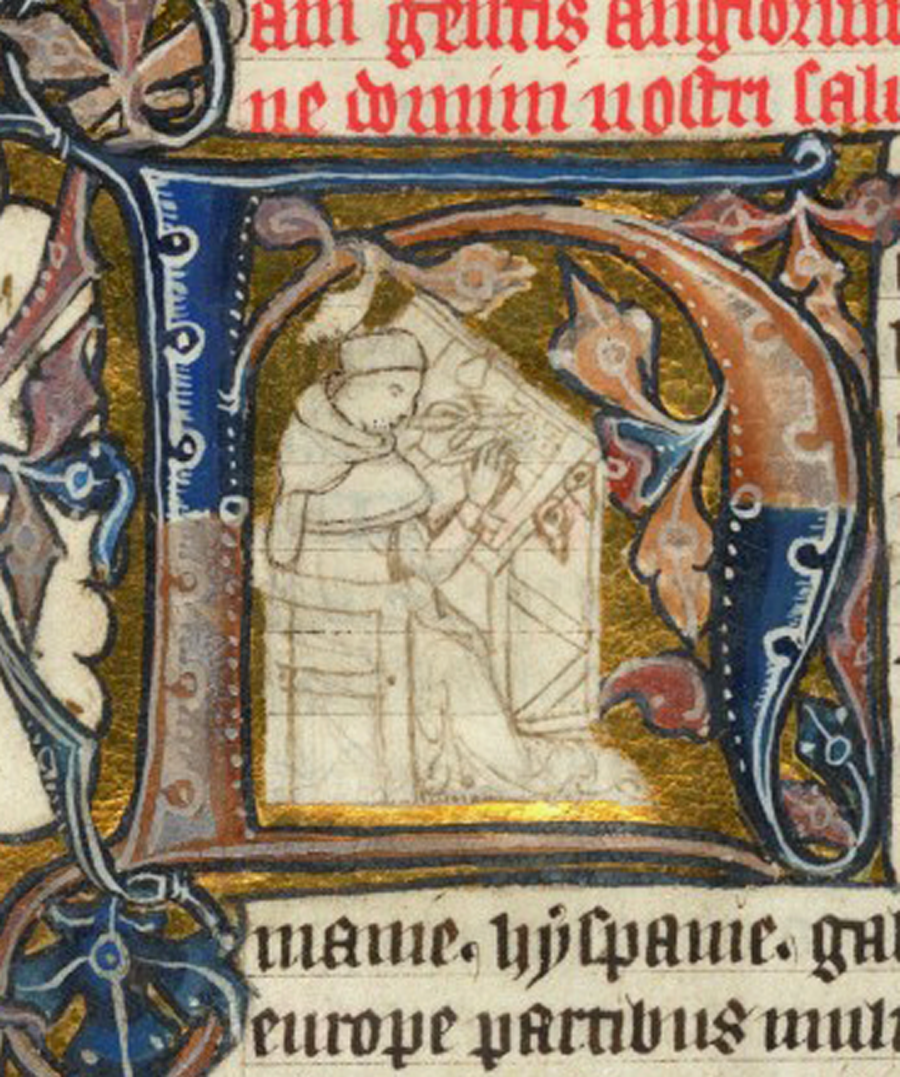

Take Will, pictured below. One day in England in the 1300s, he fell asleep on Malverne Hills and lo, he had a dream. He dreamt of Piers, a tiller of the fields.

Will’s meandering dream is the entire subject of The Vision of William Concerning Piers the Plowman, the Middle English poem written by William Langland — if in fact this person ever existed, as the author was known simply as Will of the long land.

I saw this particular manuscript the other day at an exhibit of medieval treasures from Corpus Christi College in Oxford, England. The exhibit was at the Center for Jewish History on West 16 Street in Manhattan.

Once, I read three versions (of which there are many) of this poem in Middle English. Seeing it in the original made it feel immediate, palpable. I’m not sure which version this particular manuscript is, but I think it’s what is called the B text, from about 1370. Here is my rendering of the first ten lines above, with a modern translation following:

ℑn somer seson . whan softe was þe sune,

I shoop me in to shroudes . as y sheep were,

& went wyde in this world . wondres to here.

Ac on a may mornynge . on maluerne hulles

Byfel me a faerly . of fayrye me thouʒte;

y was wery of forwandred . & went me to reste

Vpon a brode bank . bi a bornes side,

& as y lay & lened . & loked in þe waters,

I slombred in to slepyng . it sweyued so merye.

Thenne gan y to meten . a merueilouse sweuene . . .

Translation

In summer season · when soft was the sun,

I dressed in a cloak · as I a shepherd were,

And went wide in the world · wonders to hear.

But on a May morning · on Malvern hills,

A marvel befell me · of fairy, methought.

I was weary for wandering · and went me to rest

Upon a broad bank · by a brook's side,

And as I lay and leaned · and looked in the waters

I fell into a sleep · for it sounded so merry.

Then I began to have · a marvelous dream ...

Something happens when you read Old & Middle English poetry. You enter a sober tongue of plain, direct words. There are no euphemisms.

Something else happens. The words as they move about on the page pull you in. They move separately and together, on different interconnected levels. Like the geometric designs in old manuscripts, they form riddles, alliterative riddles. Reciting them out loud, you can feel the alliteration in your bones. You are in a maze.

The poets were skilled at doing what poets do best, taking a measure of the human animal, but they were also formalists, pattern makers whose word play was transmitted to them by the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) poets. Old English was rent and changed forever by the Norman conquest of 1066, but the alliteration and the plainness persisted long afterward.

The poets saw great significance in puns and riddles. Will, our dreamer, wills to embark on a journey of his will, which sleeps and wakes up throughout various parts of his long dream. The poem goes from the literal level through a number of allegorical levels — of individual will, free will, the lack of free will, weak and strong wills, the will of God, of man, ruler, religion, the cosmos — with no one level abandoned for another. Make of it what you will — really, you take the poem to whatever level of comprehension you can.

I have not found complete consensus on the "right interpretation" of this poem, but commenters agree that Will saw Piers, with his dusting of desert-father humility and his work as a tiller of the fields, as living life more honestly than many of the churchmen he knew.

In his absorbing book Status Anxiety, Alain de Botton discusses the medieval perspective of mutual dependence of the noble and the lowly. He cites Aelfric, the abbot of Enysham, who in his Colloquy of 1015 stated that peasants were the most important members of society. They could do without the nobles or the clergy, but "no one could do without the food supplied by the ploughman" (Aelfric, in de Botton, p.49). Thus was Piers the perfect subject for Will's dream.

Here's an old riddle (below) included in the Harley Lyrics manuscript (see References). The four lines look like what they are — a pattern, a Rubik’s cube, a tight form of finely fit parts. The parts can move about and by moving change the meaning. But it's a lyric (don't forget) and depends on the power of the words to express immediacy. This riddle is about earth's creation, clay taken from earth in the act of creation, our creation from earth, tilling the earth, the hardship of life on earth, why we're on earth, our return to the earth.

Erþe toc of erþe erþe wyþ woh

Erþe oþer erþe to þe erþe droh

Erþe leyde erþe in erþene þroh

þo heuede erþe of erþe erþe ynoh

Here's another interesting Old English riddle, no. 47 from the Book of Exeter (circa 960-990), an anthology of Anglo-Saxon poetry given as a gift to Exeter Cathedral by Leofric, who served as the cathedral's first bishop from 1050 to 1071. The anthology is still in the cathedral's possession. (I like this commentary I found on the riddle, which notes that the bookworm is no wiser for all the words he swallowed.)

Moððe word fræt. Me þæt þuhte

wrætlicu wyrd, þa ic þæt wundor gefrægn,

þæt se wyrm forswealg wera gied sumes,

þeof in þystro, þrymfæstne cwide

ond þæs strangan staþol. Stælgiest ne wæs

wihte þy gleawra, þe he þam wordum swealg.

Translation

Moth ate words. It seemed to me

a curious chance, when that wonder I learned,

that the worm forswallowed some man’s song,

thief in darkness the glorious speech

and its foundation. Thievish guest was

no whit the wiser for swallowing words.

(tr. © 2016 by Jonathan & Teresa Glenn)

Characters in popular old English plays with names like Daw, Coll, and Gill complain about the "gentlery-men" who keep them "hammed, / Fortaxed, and rammed" (Wakefield Pageants, see References). Play writing was one avenue in which writers could debate issues and put a mirror to society.

Friars needing a good sermon took purely secular ancient tales like those in the Gesta Romanorum (see References) and appended Christian "moralities" at the end, often stretching the moral to fit the tale. The listeners heard a good story and went home with a dollop of cosmic grace to boot. Who did the king represent in that tale of Ancelmus the Emperoure? "Dere Frendis, this Emperour̛ is oure lord Ihesu Crist; the casteƚƚ is paradys, the Stiward is Adam, our̛ first fadir, þat lost the casteƚƚ of paradys. Þe iij. knyghtes, of whom oon was strong, anoþer wys, & þe thrid amerous, betℏ thre kyndis of̘ men... " (Just so you know.)

Medieval writers made constant parallels of the human world with the natural, seasonal, and animal worlds; animals appearing in text represented human types and conditions; we could see ourselves represented as others saw us.

For every stage of human existence there was a metaphor. Nursery rhymes masked political satire. Songs for the field made the work more bearable. The calendar dominated secular and religious life, agricultural and court life.

It's not only different from how we live today, but the whole world view was the opposite of our own. There must be a reason, then, that the manuscripts have lasted, are considered precious, are being tenderly restored through technology and careful handling, and cause such notice in the newspapers. We want to know about ourselves.

Oh, the Illuminations!

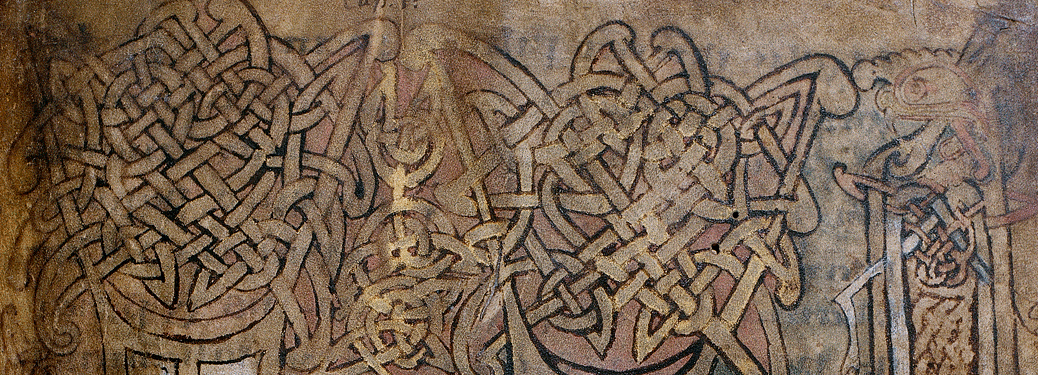

What genius made the unique art in the Book of Kells? The year was 800, the name comes from the monastery of Kells in County Meath, Ireland. Three artists, perhaps four, are thought to have completed the entire manuscript, 340 folios (680 page numbers) of calfskin vellum. We can't be sure of much more than that, except that two were great artists and calligraphers. The pages show distinct artistic styles.

The monks who made the Book of Kells, the Lindisfarne Gospels, and other early Christian manuscripts are thought to have gotten their start in St. Columba's monastery on the isle of Ionahe, or Iona, granted to Columba (Latin for his given name, Colum) by King Conall for that purpose.

Columba was born in 521 in Tyrconnell (County Donegal), Ireland, and founded his monastery on Iona in 563. In the tiny town of Straid near Clonmany, Donegal, I took the picture below of the old St. Columba's church, a parish church circa 1100 to 1200. In Colum's time it was part of a monastic settlement. Now it is going to pieces on the main road, grass sprouting on its roofless rim.

Photo copyright © Frances D. Stevens.

Carpet page is the term that describes full-art pages in medieval manuscripts, with inspiration often coming from Arabic designs that overflow with a liquid-like abstraction devoid of human representation. One of the great Kells artists, creator of the Chi Rho page below, could have been Mediterranean, Italian or perhaps Mozarab from Spain, as his designs incorporate the dots, diamonds, and spoke-like roundels found in Arabic art throughout the Middle East.

Or not. Irish monks sailed back and forth freely from Middle Eastern countries and came to master their design elements, just as they mastered the almost impenetrable geometric patterns of their Anglo-Saxon neighbors.

Used by permission.

Another Kells artist had an exquisite calligraphic style. He had a love of strong color, blues, yellows, and greens of striking depth and beauty. His work shows an Irish first-initial flourish and whimsy mixed with the maze-like intricacy of Anglo-Saxon geometric design, in which the viewer can get lost. The beauteous (part-) pages below are likely his.

Used by permission.

Used by permission.

The Kells artists — in edges, in corners, and woven into their mazes — painted a gloriously playful mix of animal and human depictions hiding in plain sight, in colors so magnificent you wonder how they did it. They painted Christ, heavenly hosts, demons, the evangelists, people they knew and people they didn't, themselves and each other, and a full range of animals and zoomorphic creatures. They criss-crossed, folded, pleated, and braided them into the infinite patterns they are famous for.

Can you find the figure on the right side, bottom half, of the carpet page below? Do you see the frown on the left-side figure balanced by the smile on the right-side figure in the next image?

Used by permission.

Used by permission.

The artists' whimsy, and their glorious use of color, certainly provided relief from the solitary concentration required to produce such books. Perhaps the art gives a hint that life in the monasteries was far more than a boring sentence of work, silence, and obedience. The monks were sophisticated travelers who knew what was going on in the Mediterranean and the north Atlantic coast. They were multilingual. Their monasteries held their islands' treasures.

Listen to what Gerald of Wales (i.e., Giraldus Cambrensis) said in 1188, in his book Topographia Hiberniae (Topography of Ireland, written for Henry II), about the Book of Kells:

Look at it closely and you penetrate into the greatest secrets of art, you will find there ornaments of such complexity, such a wealth of interlace knots and lines that you would think it the work of an angel rather than that of a human being. (G.C., Ch. 38, Of a book miraculously written; see p.55 of the pdf.)

How did the artists achieve such consistently, brilliantly dizzying patterns? They used magnifying lens, which let them paint intricacies that an untrained eye can miss. It reminds me of using the Photoshop software to work on one pixel at a time to get the exact effect you want. Eyeglasses weren't invented yet, but lenses made from polished crystal, usually quartz, have been dated back as far as 750 BC and were probably used much earlier than that. It isn't mysterious; the monks knew about these products and knew where to get them. (Wikipedia gives a nice overview on the history of optics.)

What about the colors? A Book of Kells information site describes a 2009 pigment analysis of the manuscript's colors done via Micro-Raman spectroscopy, which works with microscopic areas of larger objects. The study found that [I have left out the chemical symbols in the quote below.]:

[T]he red-orange was made with red lead. The yellow pigment was made with ... yellow ochre. The green pigment was made from verdigris, and the blue pigment was made from indigo. Purple pigment was present in the form of orecin, which is a substance derived from the lichen Roscella tinctoria. The black pigment was made from iron gall ink. Finally, white pigment was present in two forms, gypsum anhydrite and bassanite.

To make these colors, the artists had to be familiar with where and how the materials could be gathered and the processes to refine them into inks and colors. They had to know how to prepare the vellum and how it took to the inks. This was a sophisticated undertaking.

The Book of Kells is the finest example of the Irish "insular style" manuscripts, as they are called, of 600-800. The art mixes Middle Eastern and Anglo-Saxon motifs to create works the likes of which we haven't seen before or since, anywhere. Later medieval books are artfully illustrated with initial letters and page-long designs, but the art primarily depicts the subject matter (like the illustrations of Bede and Will the dreamer above) and does not have the intensity, genius, and joy of the early works.

The Book of Durrow, the oldest known illuminated manuscript in Ireland, was made in 650 either at Durrow Abbey in central Ireland, or in a monastery in Northumbria, England, or on the isle of Iona. It predates Kells by over a century.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, written circa 698-721 by Eadfrith in his monastery off the northeast coast of England, on isle of Lindisfarne, and probably illuminated by him as well, is another exquisite example of this art.

The Book of Dimma, late 700s, was produced at St. Cronan’s Monastery in Roscrea, Ireland, not far from Durrow. The Book of Mulling, or Moling, circa 750-800, was produced at St. Moling's monastery on the banks of the River Barrow in southeast Ireland.

The Garland of Howth, late 700s-early 800s, is from Howth, near Dublin, on the Irish Sea. The Book of Armagh, which contains information on St. Patrick (387-461) as well as a literary history of Ireland, was written by the monk Ferdomnach in 807-808.

The slideshow below has some pages from the manuscripts mentioned above. There is a short and very good video on The First Book of Ussher on YouTube. There are videos on the Book of Dimma and the Book of Mulling that are also very informative. This Pinterist website is full of some of the most stunning pages from the early books. You should also go to Trinity College Library's website where you can go through the Book of Kells page by page and enlarge the pages to fully appreciate their technical brilliance.

What Do I Mean, Mindful?

I mean that in the early middle ages, it was hard to live a step removed from your own life and from the people who are important to you. We have so many wonderful things now, but we could be a little better at judging what we really need/want and really don't need/want. The material from the middle ages has a quality that I'll call here-ness (immediacy). You don't have to read ninth century riddles or listen to songs from old Andalusia (but they're nice). You just need to understand what you need really, and what you need virtually.

The medieval mindset was so different from our own, that at first glance the old days can seem not only distant, but irrelevant. I guess any time that isn't our time can seem irrelevant. I also second-guess myself from necessity. Early medieval society was not democratic. Upward mobility was a longhaul. New discoveries were not always welcome.

If I lived in England in 800, I like to think I'd have been a scribe, preserving culture, or an astronomer, advancing it. Then I remind myself that scribes and astronomers were men and I probably wouldn't have been allowed to do such things. (I might have enjoyed flamenco dancing in Andalusia.)

On the other hand, life was what it was. It wasn't virtual. Medieval virtual reality existed in the imagination, and no one confused the two. With our extravagant increases since then in knowledge, lifespan, wealth, and opportunity for the formerly-left-out, we should have more, not less, appreciation of reality. But we don't.

What is bogging us down? There's an awful lot of noise these days. So many facts to consume, so much not knowing which facts are important and which aren't. So much streaming in from the outside telling us who we are and what we should do. So much pressure to prove that we fit or don't fit certain algorithmic models so we can be the right person.

Not that we want to, but we're losing our minds, our mindfulness, as if we don't even know any better. We don't even think it's not a good idea to not know or remember important things, because we can always find them out on the Internet. And if we can't find what we want there in ten seconds, we get frustrated.

I'm not saying we should embark on a mindfulness crusade. It's just that our work and daily lives don't demand that we concentrate as much as we once had to.

To concentrate is to focus the mind. Think about those ancient poets and teachers who had nothing but their memory bank to contain huge amounts of knowledge. They had an important job, transferring knowledge from one genertaion to the next. We wouldn't have cultures and histories if they hadn't done that. Using memory as a learning tool is now considered subpar and uncreative, but how can you be creative if you've never been taught to focus your mind?

In grade school (mine was K-8) in the late 1950s and 1960s, I had to memorize times tables and math formulas, vocabulary spellings and definitions, Latin and Greek roots, prefixes and suffixes, poems and one-page speeches (and the Baltimore Catechism). In eighth grade, we had to pick out specific subjects and type out full-page bibliographies for them, using the different bibliographic styles for books, articles, translations, etc. And oh did we diagram compound-complex sentences (with future perfect tenses)!

The mind is an interesting place. No sooner do you focus strongly than you're in a different place from where you started. That's how thinking, awareness, and discovery work — like the words in those interconnected layers in old riddles, moving, wavelike, up, down, and through each other. Not to sound like an athlete of God, I have no desire to meditate in the desert, but we don't really know what we think until we give our minds the time and space they need to clue us in.

The French writer Colette's intense and spirited heroine Claudine was known to exclaim, "I am Claudine!" She didn't suffer from anxiety not-otherwise-specified, what de Botton calls the fear "that we are in danger of failing to conform to the ideals of success laid down by our society and that we may as a result be stripped of dignity and respect" (p.vii).

We can't blame it all on the Internet (just some of it). The idea that memory isn't as useful a tool as it's been in the past came along before our reliance on our devices. Group learning and the non-specific, excitable quality "creativity" have been all the the rage since the mid-1990s. My son's elementary school (K-5) PTA was fixated at that time on having a banner headline for the PTA newsletter, which I edited. I suggested a heading containing the phrase "ABCs", another with the term "Building Blocks." Everyone rejected them both so quickly it was a nonissue, and the consensus was "Learning Through Creativity."

In 1998 I found a book called The Capuchin Annual 1948 on a bookshelf as I was cleaning out the house I grew up in. My dad was deceased, and my mom was moving. Both were readers, but this book was a little different, edited by a Father Senan, published by Dublin: Church Street, ten shillings & sixpence. The cover was gone and the binding was in bad shape. My dad probably found it in a used book store, but he had no interest in Capuchin monasteries. I saved it. (I've since seen it on abebooks.com.)

It has 630 pages, stuffed with interesting things. There is a 21-page section of photos by T.J. Molloy entitled "A Kerry Triangle," of castles, cathedals, memorials, landscapes and seascapes, homes and children, ploughs in the fields, the McKenna's Fort where Roger Casement was arrested. There is a 65-page "symposium of tributes" on the actor F.J. McCormick (1889-1947) with 28 full-page photos of his work in Dublin's world-class Abbey Theater. There are eight pages on the poet Thomas Moore.

Frances D. Stevens

There are hand-done illustrations throughout. The many pages of ads include 38 pages that have, on each page, one or two pictures of people who are important for their service to country, artistic accomplishment, or other talent, along with short biographies (Joseph Tomelty, Irish playwright and actor; Cathal O'Byrne, "Belfast man of letters"; Una O'Connor, actress; Sèamus MacManus, Donegal writer, etc.) — about 70 such in all.

There's more: more photography, poetry, fiction, biography, music, history. Relatively little space is given over to matters of Capuchin life itself. There's even an article called "Sunny Days in Hollywood, California," by the above-mentioned Cathal O'Byrne. There are long articles written completely in Irish, untranslated.

Two things are otherwise interesting. The first is that there are several small humorous illustrations, like the ones at right, of the Capuchins going about their daily business that remind me of the humor of the Lindisfarne and Kells authors, who inserted figures and animals in unlikely places. The second are the full-page color depictions of saints that recall medieval iconography, with captions in Irish, and with several-page accounts of each of the saints' lives.

There are five such accounts in this volume. They start with St. Senan, circa 600. They are full of Irish history and stories of the type the early monks recorded in books like Book of the Dun Cow. The image above is of St. Lawrence O'Toole, 1128-1188; it is accompanied by accounts of his childhood, the state of politics in Dublin in Lawrence's time, historical facts about other people in his life, and lots of other information.

It's as if the book's forebears were those early works, as if some epigenetic cultural strain to record carried through. If anything, it's mindful.

References & Works Cited

Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book. Wikisource Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 2014. This online version of the riddles has riddle no. 47 above as no. 42, so go to no. 42.

The Book of Kells, a website with a section on Micro-Raman spectroscopy.

Geoffrey Chaucer, "A Treatise on the Astrolabe," The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. F.N. Robinson (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1961.)

Colette, The Complete Claudine, tr. Antonia White (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1976).

Alain de Botton, Status Anxiety (Vintage International, 2005).

Gesta Romanorum, or, Entertaining stories invented by the monks as a fire-side recreation and commonly applied in their discourses from the pulpit. (New ed., intro. by Thomas Wright, Esq. London, 1824).

Giraldus Cambrensis, Topographia Hibernica (The Topography of Ireland) for Henry II, 1188. tr. Thomas Forester (Ontario: In parenthesis Publications). This translation's Table of Contents shows the admixture of magical thinking and science in a vivid and entertaining way (and makes one thankful for real science).

The Harley Lyrics, MS Harley 2253, circa 1314-1325, ed. C. L. Brook. (Manchester Publishers, 1968). The lyrics are online.

William Langland, The Vision of William Concerning Piers the Plowman, vols. 1 & 2, ed. Walter Skeat (Oxford Univ. Press, 1924, 1961). This text is available online.

Alois Richard Nykl, Hispano-Arabic Poetry and Its Relations With the Old Provencal Troubadors (Baltimore: J.H. Furst Co., 1946).

Josefina Rodriguez-Arribas, at a conference on the medieval astrolabe at the Warburg Institute in London, 2014.

The Wakefield Pageants in the Townley Cycle, ed. A.C. Cawley (Manchester Univ. Press, 1971). "The Second Shepherds' Play" refers to the second play that the shepherds put on, not the play's characters. It's a nativity play with raucous intevals that have nothing to do with the Christmas pageant. You can read about the play online.

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!