Colleges and Universities:

New Peddlers of Subprime Mortgages

It is probably not much of an exaggeration to say that there is a unanimity that the Great Recession of 2007 is the most significant financial disruption witnessed in the United States since the Great Depression. But what is more significant is that most parties believe that the direct trigger for this financial calamity was the phenomenon of subprime mortgages. These were the highly profitable mortgages that financial institutions could not produce, package, and sell fast enough.

The profitability associated with these mortgages, sold to households and individuals who could not afford them, is best illustrated by what Charles Prince, CEO of Citibank at the time, told a Japanese interviewer: “As long the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance. We're still dancing.” His statement shows a certain moral depravity. It simply says that the great United States financial system could not stop knowingly exploiting a large segment of U.S. households as long as the sham operations produced great profits and even greater bonuses.

But what might be surprising is that almost the exact unethical operations are being liberally applied in a field most would not associate with financial shenanigans—that of higher education. Of course, not all students are "subprime" students, in the same way that not all mortgages were subprime and designed without regard to whether the applicant could carry the implied burden of financial commitment if real estate prices stopped increasing. However, student loans have grown to represent over $1.3 trillion, an amount larger than all credit card debt put together.

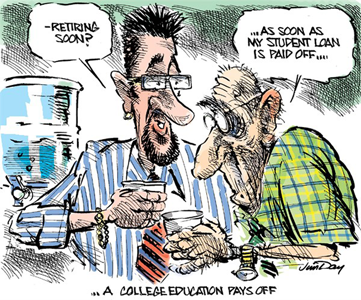

Not only that, student loans carry onerous terms that do not permit refinancing at lower rates and do not allow bankruptcy under any set of circumstances. Many of the students who carry such loans become in effect indentured labor. They will have to spend most of their working lifetimes meeting the ever-growing exponential debt that they accumulate prior to graduation. In many cases, a student will never be able to start a family, buy a house, save for retirement or take a vacation, since the annual interest on the loan is greater than the annual payments that the student can afford.

So how is this similar to subprime? In many colleges, thousands of colleges, the number of administration staff and their compensation has been on the increase, and faculty remuneration has grown along with expenditures on fancy new dormitories, luxurious sports facilities, expensive food courts, and an increasing number of course offerings. The bill for all such expenditures that are nonacademic in nature is carried by the student whose fees and tuition have grown beyond the increase in wages and inflation.

Many of the students who carry such loans become in effect indentured labor. They will have to spend most of their working lifetimes meeting the ever-growing exponential debt that they accumulate prior to graduation. In many cases, a student will never be able to start a family, buy a house, save for retirement or take a vacation, since the annual interest on the loan is greater than the annual payments that the student can afford.

Higher education has become much less affordable. These (at best) academically superficial expenditures would have forced a substantial increase in the average tuition if admission were limited to academically qualified students. But what are the chances that the academically well-equipped students would accept paying, say, twice the current rate of tuition? Not very high, especially in an economic environment in which the current cost of higher education is being questioned.

The apparent adopted solution to this paradox is simple but highly unethical.

Once the financial industry could not find enough eligible takers for its mortgage products, it lowered the standards, and then lowered the standards again until it had no standards. (No income and no job requirement demanded from mortgage applicants). Colleges and universities are using an identical method of lowering admission standards to meet their enrollment goals, to ensure that their planned, additional nonacademic expenditures can be met. As a result many colleges and universities have adopted the practice of open admissions, whereby the student must demonstrate an ability to make the required payments, usually through a combination of loans and grants.

But often these are the students that do not stand a meaningful chance of graduating in either four or even six years. Many of these students are offered admission to undertake an academic program that they are not equipped to handle, just as banks offered subprime mortgages to individuals when it was clear from the start that the mortgages in question were beyond their ability.

In many colleges only 30 percent of students graduate in four years, and only about 50 percent in six. Often these students are encouraged to take loans of about $10,000 a year. You do the math. Half drop out with loans of $30,000 to $50,000 and an annual interest rate above 6 percent, when the prime rate is under 3 percent and the short-term rate is under 1 percent. These students have been deceived. The universities and colleges that have helped them accumulate this debt can be accused of having violated consumer protection laws by not making clear the high degree of risk associated with such loans.

Unfortunately, this is not the whole story. Many of the students that graduate in, say, six to seven years with a potential debt burden of $100,000 end up working in jobs that pay $35,000 per annum in a city such as New York, Boston, or San Francisco. These students would be lucky to be able to afford a monthly payment of $250 toward their student loan balances, the interest on which accumulates at the rate of over $500 per month.

Many of the financial institutions that participated in the subprime sham have been penalized by the markets, have had to fire some of their senior staff, have had to meet stringent new financial regulations, and have been fined billions of dollars. Yet the higher education establishment still goes about its business of recruiting students, many of whom are destined to fail, knowing they are taking advantage of the naiveté of these young adults and their parents but looking the other way, because it allows them to go on building luxury dorms designed by star architects and allows salaries and the number of nonacademic, and occasionally academic, staff to increase.

Pity a nation (with apologies to Gibran) whose institutions of higher learning have become effectively the new peddlers of subprime mortgages.

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!