The Potion?

It's Not What You Think.

City Art Centre, Edinburgh, Scotland

Let all men in their thoughts gaze only at Ireland, let their eyes take pleasure there and see how the new Sun following on its Dawn, Isolde after Isolde, shines across from Dublin into every heart. ... Whoever looks Isolde in the eyes feels his heart and soul refined like gold in the white-hot flame. ... she adorns and sets a crown upon womankind.

—Gottfried, p.151

The medieval tale of Tristan and Iseult exposes elemental, urgent passions and needs. Sometimes the struggle with them is ferocious. Sometimes the struggle is simply to stay alive.

Large fragments survive of three versions of the story written between about 1160 and 1213 − those of Beroul and Thomas in the Anglo-Norman tongue of their native Britain, and Gottfried of Strassburg in German. They wrote with love for their characters and empathy for their suffering.

The authors did something else. They gave us characters with sophisticated thought processes and careful self-awareness. Thomas and Gottfried created a new kind of story, to be read privately, not simply recited as reliable entertainment at court. They worked within the tale’s constraints of Celtic mythical elements and European courtly norms, but they (like other great medieval writers) set the tone and standards for their compositions. What each created was a literary work whose probing into the shadow world of human emotions, motives, and behavior presages the great novels of later ages.

Even Beroul, whose version is the oldest and most enchanted, interjects his feelings at pivotal junctures in the narrative so that we know where he stands. When, for example, the evil dwarf Frocin insists that King Mark banish Tristan or lose the support of his own court, Beroul inserts into the text, “Cursed be all such magicians! … May God curse him!” (Beroul, p.61)

Ideas can be mischievous, compelling, they can steal us away, assuming a life of their own until we start thinking they’re true, forgetting that our introduction to them was simply as an idea. You can read reviews or hear a speaker on a particular work and then feel you understand the work, without ever actually reading the text! This is doubly true of books from long ago and far away. But trust the Tristan text, it will tell you what the story is about.

The story is about a society whose values do not support the people who must uphold them. The advantage of looking at this story from an 800+ year perspective is that its world starts to appear as in a fishbowl, despite its intelligent and cultured inhabitants. Even Queen Iseult doesn’t have magic enough to provide relief from the stifling jealousy, hatred, and selfishness that destroy the main characters. In the end, ugliness wins.

Kings and Queens,

Giants and Dwarfs

Who are the fish in the bowl? Mark of the horse’s ears (it is said), Mark “the waverer,” to whom “one woman was as another,” the “artless” king of Cornwall. Tristan of Parmenie, prophetically named by his dead parents. Queen Iseult, the healer who loves Tantris/Tristan and wants him for her daughter. The daughter Iseult, tutored by Tantris in all the worldly arts and made more whole. The giants, dwarfs, and courtiers to be slain, outwitted, run from − Morold, Orgillus, Urgan li vilus, Frocin, Marjodoc, Melot, Gandin, Cariado, and others bent on destroying the lovers and debasing the authority of Mark. Tall and handsome Dwarf Tristan, who leads Tristan into the battle that secures his fatal final wound. Iseult of the White Hands, she who proves that a jewel cannot be replaced by a stone of outward resemblance. Brangane, Iseult's cousin, who remains constant until she bends in helpless anger. Curvenal, Tristan's childhood tutor to whom he owes his elegant education.

Tristan the Minstrel

With his abduction at age 14 by Norweigan merchants and subsequent landing on Cornwall’s shores, we see the “homeless” and “landless” Tristan come alive. The handsome boy is multilingual, adept in courtly arts, brave in battle, all while still a child. He at once inspires admiration and jealousy. The hostility of Mark’s court toward Tristan starts very soon after the youngster finds his way to the castle at Tintagel. This is an important fact, because Iseult is at this point nowhere in sight.

But it is as a minstrel, and he is most of all a minstrel, that Tristan wends his solitary way. His influence on others as manifest in his years with Mark before setting out alone for his first trip to Ireland is not diplomatic, not chivalric; it is emotional. He is a projection carrier for the layers of society he moves among, reading the hearts of lowly and great alike with his harp and his lays.

He made such excellent sweet music on his harp ... that many a man sitting or standing there forgot his very name. Hearts and ears began to play the fool and desert their rightful paths. ... Nor was there sparing of eyes: a host of them were bent on him, following his hands ... Oh, what kind of child is this? What companion have we here? (Gottfried, p.90)

13th Century tile, British Museum. Used by permission.

This influence grates on the mean-spirited people around Mark, none of whom are brave enough to put their lives on the line for anything important. Mark’s men are too afraid to face the Irish giant Morold who has been stealing the children of Cornwall, so Tristan faces alone a harrowing fight to win them back. But Tristan’s many gifts to society are taken for granted and finally resented, and his gut responses to injustice as well as his ability to please with music are called “secret arts.” The barons want Mark married with a proper heir to prevent Tristan’s rise, even though his natural uncle Mark wants Tristan to be his heir and has stated he has no wish for a wife.

13th Century tile, British Museum.

Used by permission.

Tristan is 18 years old when he makes his first trip to Dublin. He's desperate, and he believes the Irish queen's healing powers are his only hope of recovering from the mortal wound to his loin suffered at the hands of the giant Morold. It's delicate—Morold is the queen's brother. Tristan must plan carefully. He will take only his harp and wear the humblest of clothing. He will be Tantris, a minstrel attacked by pirates who has lost his way, drifting alone near the Dublin shore in a small skiff. The trip is a gamble and he has no guarantee that he'll survive. He's given Curvenal and Mark instructions in the event he never returns.

To gain the Dubliners’ trust, he plays his music for them though his heart is not in it and his wound is killing him. He tells them:

In this way I have been drifting alone in pain ... for well of forty days and nights, wherever the wind buffeted me and the wild waves bore me … (Gottfried, p.142)

Whatever he could do to win their favor [with his harp], this was his desire, to this did he put his mind and this did he accomplish. (Gottfried, p.143)

Tantris, he who relies on his wits, wins their favor. Thus he journeys to the Iseults, to healing, and (it turns out) to falling in love. The queen regards his temperament, his talents. She heals his wound and bids him stay to tutor her daughter Iseult—in languages, worldly arts, courtly manners, in all he knows. She trusts him even though she and her daughter find proof of his murder of Morold. Tantris and Iseult spend six months together, close together, and they fall in love. Not that they meant to, not that they are yet aware of it, but they are both in their late teens, and their hearts are astir.

This is a natural event, yet there are critics who would have us believe their union is a mistake, a disruption of the social order, all because the story employs a mere (but handy) literary device—the love potion. Perhaps the queen thought her daughter would sorely need this potion because she could see with her own eyes who her daughter really loved, perhaps she was trying to make it easier for these mortals so at the mercy of, and duty-bound to, courtly convention.

Iseult la Blonde,

Yseut the Fair

Who is Iseult? She is Iseult (Irish), Yseut (Beroul, Thomas of Britain), Isolde (Gottfried, German), Esyllt (ancient Welsh), Iseut (medieval English) , Eseld (Cornish), Ysolt (Celtic), Yseult (French), Ysonde (English), Isoude (Scottish). (She is also Issy, short for Iseult, sister of Shem and Shaun and daughter of H.C. Earwicker and Anna Livia Plurabelle in James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.)

Who is Iseult? She is the equal of Tantris/Tristan, a music-maker who unwittingly reads the “hidden and unseen” thoughts of others, who lives by her wits in a strange land, who gives herself to a husband who occasionally sends her off to die, like Tristan versed not only in worldly arts, but in what Gottfried calls Bienseance. What is this?

Its teaching is in harmony with God and the world. In its precepts it bids us please both, and it is given to all noble hearts as a nurse, for them to seek in her doctrine their life and their sustenance. (Gottfried, p.147)

But no one in Mark’s court, including Mark, has any sense of Iseult except as a social necessity, the king’s wife. She is fair game. And as with Tristan, her comeliness and magnetism work against her.

She sang her “pastourelle” … well, well, and all too well. For thanks to her, many hearts grew full of longing …

But her secret song was her wondrous beauty that stole with its rapturous music hidden and unseen through the windows of the eyes into many noble hearts and … took thoughts prisoner suddenly, and, taking them, fettered them with desire. (Gottfried, p.148)

2 Temple Place, London.

I am reminded of Rebecca Solnit's notion, in A Field Guide to Getting Lost, that beauty can seem "like destiny or fate or meaning" but may be a gift "given by the sinister fairy at the christening." As the poem progresses, Tristan alone values Iseult as a full-fledged individual. Mark the waverer is lost to the rabid machinations of his barons, who over time degrade Iseult to the level of a medieval sex symbol, hardly one inspired by Bienseance. The barons "taken prisoner" by desire against their will do not understand their emotions and feel overcome with jealousy, revenge, and desire.

The Tristan authors, however, whose story this is, let us know where they stand viv á vis the lovers:

I have thought much about the pair of them, and so do now and ever shall. When I spread Longing and Affection as a scroll before my inward eye and inquire into their natures, my yearning grows … as if it would mount to the clouds. (Gottfried, p.203)

Even as Iseult becomes an object to ogle; as Gandin steals her from Mark, who just stands there; as Marjodoc, the steward-in-chief, gloats at finding her in bed with Tristan; as the hateful Melot applies his snares morning and night to catch her with Tristan; as Mark hands her over to a colony of leering lepers to be abused at their will; as Mark exiles her and Tristan, who, hunted, flee to a forest for three years and who, in Beroul's version, sleep every night in a different location, their clothes ragged, foraging for food, thin and frail; as Mark puts her through the Ordeal of Fire; as Cariado maliciously woos Iseult in mockery of Mark and at Tristan's expense; even then, she maintains her wits and stays true to Tristan. Her faithfulness to him, not her unfaithfulness to Mark, is the source of the barons’ despicable jealousy.

Why would the 18-year-old girl want to marry an older king she never met? Iseult wasn’t interested in money, power, or adventure. Both Iseults know it was Tantris who slayed the dragon when he returned a second time to Ireland and that the dragon slayer “wins” Iseult. Both are protective of him; even the queen’s husband King Gurman quickly forgives Tantris Morold’s death and welcomes him like a gift of fortune.

The girl is in love:

Isolde kept on looking at him; she scanned his body and his whole appearance with uncommon interest. She stole glance after glance at his hands and face; she studied his arms and legs … she looked him up and down; and whatever a maid may survey in a man all pleased her very well, and she praised it in her thoughts. (Gottfried, p.173. Emphasis mine.)

She makes a prayer in her heart that is nothing if not a wish for marriage with Tantris, knowing as she does that she has a kingdom to offer this poor merchant:

Oh Lord … there is a failure here, in that this splendid man … should seek his livelihood wandering so precariously. By rights he should rule a kingdom or some land of suitable standing. (Gottfried, p.173)

For his part, Tantris/Tristan is lost in Iseult, beside himself when he returns to Cornwall and sings her praises to Mark and the court (see also opening quote).

Tristan had resumed his life, with a joyful heart. A second life had been given him, he was a man reborn. Only now did he begin to live. (Gottfried, p.152)

And all of this is way before they drink the potion together!

Oil on canvas. Used by permission of the artist.

www.facebook.com/Marc-Fishman-107533946000148/

Mark of the Horse’s Ears,

His Treacherous Court

Mark, so lonely a figure with no real friends, has no interest in Iseult. Manipulated by his barons to agree to marry, “never dreaming that it would ever come to pass” (Gottfried, p.153), he submits. Tristan, trying to save his own skin, says he’ll make the barons “see for themselves whether it will be my fault, if this land should remain without an heir.” (p.154) For the courtiers, the whole situation is jolly good sport.

The name Mark comes from the Celtic word for horse—Margh in Cornish, March in Welsh (e.g., the Welsh marchog means horseman). In Beroul's more elemental version of this story, the dwarf magician Frocin is responsible for giving Mark horse's ears, and for betraying him by giving away this embarrassing secret to the barons. This episode does not appear in the refined psychological versions of Thomas or Gottfried, yet this encumbrance of Mark’s corporealizes his affliction—his lack of valor, his indecision.

With the lovers' return from their three-year exile in the forest, Mark at first wants to pretend that everything is normal, but he eventually simply bans them from contact. Mark's lot is woeful, he is not evil, just artless, as the poets say. Nor does he love Iseult, only “the beauty of her throat, her breasts, her arms,” because this is what his society values.

He possessed in his wife neither love nor affection, nor any of the splendid things which God ever brought to pass.

…

Oh, how many Marks and Isoldes can you see today … who is to blame for their blindness? … It cannot be said that one is deceived or outwitted by one’s wife where the fault is manifest. (Gottfried, p.275)

…

I am convinced that if one wrongs a willing heart so long that ill treatment robs it of its fruitfulness it will yield worse ills than one that was always evil. (p.277)

Which is what happens. Angry that the lovers still contrive to meet, Mark goes into surveillance mode. He employs Marjodoc to scheme against Iseult. Marjodoc then hires Melot as a spy, who “applied his lies and snares to this task, morning and night.” Mark offers rewards for trapping the lovers; he

privately charged the dwarf to spread his lies and strategems around the lovers’ secret doings, and assured him of his lasting gratitude. (Gottfried, p.2xx. Emphasis mine.)

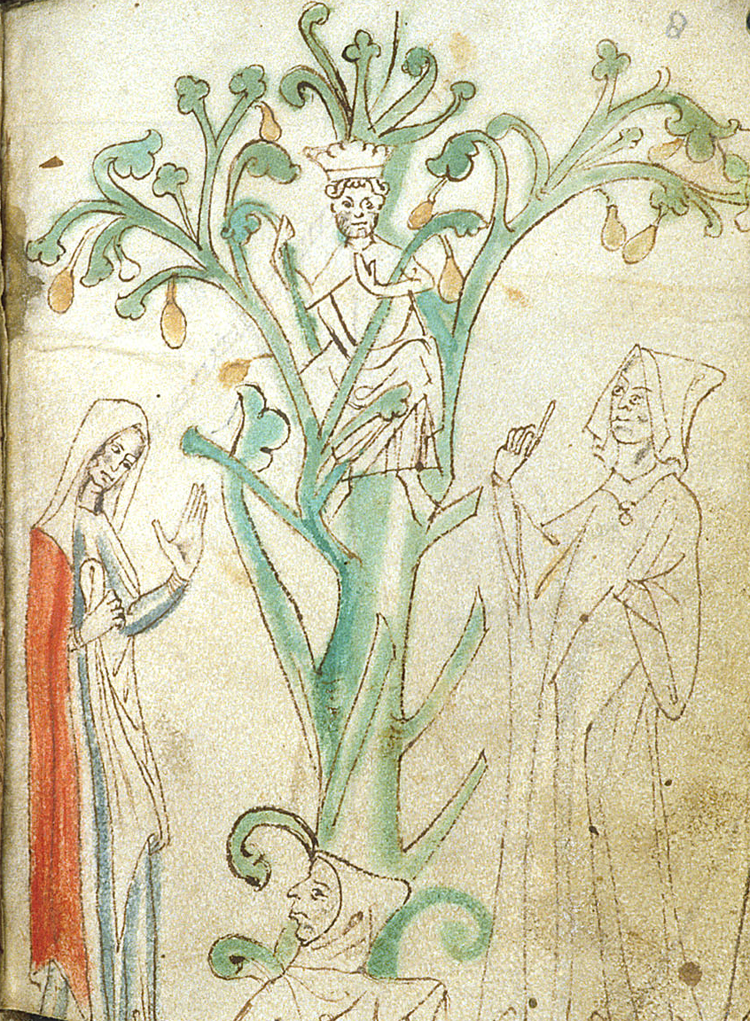

Alain of Lille,13th Century manuscript.

British Library, London.

Iseult’s position goes from helpless to depraved, bereft of even a bit of dignity. Mark's spies finally prove Iseult's guilt to him, and Tristan is forced to flee, eventually arriving in the land of Arundel, a duchy near Brittany. Iseult, about 22 now, is alone with her tormentors in her loveless marriage. With "deceit in their hearts ... the one a snake, the other a cur ... cur and snake," Gottfried says of Melot and Marjodoc, the dirty tricks have done their work.

Intent to Harm,

Death of the Lovers

In Thomas’s poem, Tristan’s exile in Arundel brings on a tormented internal dialogue that goes on for hundreds of lines. He questions Iseult, himself, and God, addressing the futility of his longing for her. Will she forget him if he’s out of sight? Is it proper to satisfy physical needs if there is no love? To whom can he turn in this strange land to unload his grief? He can’t think clearly but he tries. It is the kind of mental agony beset by all points of view and comforted by none, a kind of madness.

Enter Iseult of the White Hands. Who is this girl? Daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Arundel, sister of Kaedin. Do they all have affection for Tristan? Yes, Tristan has been a brave companion to Kaedin in battle, with whom he becomes a friend. Why does the daughter have this name? Why does her beauty resemble the Queen Iseult's? He’ll never love Kaedin's sister and “would never have desired her … if she hadn’t been called Yseut.” (Thomas, l.252, 254) But she takes his lovelorn looks as signs of his affection for her and acts accordingly. The whole family would be pleased to have a marriage take place, and soon enough one does.

Tristan thought to abandon Yseut

and wipe out the love from his heart;

by marrying the new Yseut

he hoped to escape from the first.

And if it had not been for the first Yseut

he would never have so desired the new

(Thomas, l.358–363)

In his analysis of how people try to extinguish their pain, Thomas says they

take steps to extricate themselves

to free and liberate themselves

but only thereby fall further into the trap;

and often they devise some plan

which, in the end, leaves them in sorrow. (Thomas, l.397–397)

Tristan’s grief becomes White Hands’s grief. He cannot consummate the marriage, and he feels great pity for her. Alas, this was no solution, as the poets tell us.

The story reaches the finish line in a great gust of hobbling events. The seeds of revenge grow in White Hands. Queen Iseult is wasting away under a hairshirt in Cornwall, unable to eat or sleep. Tristan’s disguises—minstrel, merchant, begger, leper, cripple, simpleton—no longer provide a way to gain access to Iseult, or save her life, or his. Iseult’s faithful cousin Brangane, her only support in her loveless court, falls into a fit of rage and tells Mark that Iseult never loved Tristan and may even be plotting murder against him with the help of Count Cariado, who has come “to sue for the queen’s hand.” Mark is despondent that the nephew he loved was, according to Brangane, wrongfully blamed. Cariado does come, with his spiteful news to Iseult that Tristan is married and has no love for her any more.

Meanwhile, in a fit of urgency to see Iseult, Tristan concocts some herbs to swell his face like a leper, wears "vile garments," takes a wooden bowl and a clapper, and returns to Cornwall. The disguise and the man are now one. Queen Iseult doesn't recognize him.

Frequently he begged and rattled his clapper

Tristan saw her and asked for alms

but she did not recognize him.

He followed her, rattling his clapper

The royal servants mocked at him

... others dealt him blows

He followed them right into the chapel

Shouting out loud and rattling his bowl (Thomas, ls.1791, 1799–80, 1804, 1808, 1814–15)

This scene is piteous. Iseult panics when she finally recognizes the beggar's bowl, one she gave Tristan long ago, and drops into it her ring. Tristan seems already at death's door.

He was greatly weakened by his hardships,

the frequent fasting, the many sleepless nights.

... Tristan lay languishing below the stair

... rattling his clapper ... (Thomas, ls.1870–71, 1873)

In Arundel again after being shown mercy and helped on his way, Tristan gets a visitor—Tristan the Dwarf from the march of Brittany, who has a request. Help save his lady from the giant Orgillus! This is a curious incident, as the dwarf is "tall and well-built, fully armed and a handsome knight," says Thomas. Tristan defers at first, but out of pity for this knight agrees to take on the giant Orgillus, who gives him his final wound to the loin. As with his initial wound from a giant, there is only one healer, Queen Iseult of Cornwall, who inherited the healing gift from her mother.

This poem belongs to its writers, who are often forgotten in our rush to opinion and analysis. The poets were addressing society's top tiers, the ruling class, the people at court who listened to their works and had them copied for their own private reading. The story as told by these earliest authors is that something is rotten in courtly society, where the sport of rancor and odium among the ranks kills the life force. Everyone is out for himself, no one is happy for another's good fortune, and no one trusts the other. Nor can you take a woman seriously.

My response to this story hasn't changed since I first read it in 1976, when I thought that Gottfried's work was a kind of indictment. The story is full of mythic and archetypal elements that have been dissected, analyzed, advanced. But that kind of inquiry is separate from authorial intention. Medieval writers didn't have a literary tradition in our modern sense, they didn't have Shakespeare, Emily Brontë, Dostoyevsky, but they used the popular stories as their base to create great literature that is a mirror to society. This is what poets do. In his essay A Defence of Poetry, Percy Bysshe Shelley called poets "the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present ... the unacknowledged legislators of the world."

Public domain image, private collection

In the end, ugliness wins. The poison from the wound spreads through Tristan's body. Kaedin manages to get word to Iseult the healer, who manages to set sail in the still of night, to cure Tristan. No more ruses, she just leaves, there is no time to waste. But White Hands will have her comeuppance, finally. She lies to Tristan, tells him Kaedin is returning without Iseult, and he succumbs to his wound. Iseult finally arrives, throws herself on her dead lover, and dies of grief.

The characters Iseult and Tristan have inspired many artists. This page shows some; go to Painting is silent poetry to see more.

Works Cited

Beroul, The Romance of Tristan (Penguin Classics, 1970), tr. Alan S. Fedrick.

Gottfried von Strassburg, Tristan (Penguin Classics, 1970), tr. A.T. Hatto.

Thomas of Britain, Tristan (Garland Publishing, 1991), tr. Stewart Gregory.

Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost (Penguin Books, 2005).

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!